The Butterfield Family

Daniel Adams Butterfield and his wife owned property just south of the Payne estate. He is linked to the Payne estate because he was the brother-in-law of Alexander Holland, who with his wife Sophie Parker Butterfield, owned the Waldorf section from 1869 until 1884

The American Express Company was a merger of several companies. Henry Wells (1805-1878) started in the express business as an agent for Harnden's Express, running from New York to Albany, while in his mid 30s. In 1843, he started his own firm which carried letters for one-quarter as much as the government charged. His Wells & Company ran a route form Buffalo to Detroit, the first express company to venture west of Buffalo.

One of the employees at Wells & Company was a young messenger named William G. Fargo (1818-1881), who eventually became Wells' partner. In 1850, Wells & Company joined with two other express companies, including one run by John Butterfield to form the American Express Company with Wells serving as its president from 1850-1868. American Express covered the eastern sector of the United States while Wells, Fargo & Company formed in 1852, covered the western sector. John Butterfield (1801-1869) began his career in the express business as a stage driver and soon owned a portion of the business. Through deft maneuvering, he soon controlled most of the stage lines west of New York and in 1849, he formed Butterfield, Wasson & Company. In 1850, he merged his company with two rivals, Wells & Company and Livingston, Fargo & Company, to form the American Express Company. In 1857, American Express received the government contract for the first transcontinental stage line at $600,000 per year and resulted in the Overland Mail Company of which Butterfield was president. his activities stretched to steam boating, plank roads and railroads.

Frequent travelers in the American Southwest will inevitably come upon historical markers for the Butterfield Overland Mail in the most disparate locations, from west Texas to central California.

Known to most as the Butterfield Stage, this precursor to the Information Superhighway initiated communication across 2,000 miles forbidding desert and mountain wilderness, providing isolated Westerners with their first regular news and mail just prior to the Civil War. It was named for its owner, John Butterfield.

John Butterfield was born in Berne, New York in 1801 and grew up on a farm amidst the technological revolution of the first steamboat, the Erie Canal, the steam locomotive and the electric telegraph. He was the son of Daniel Butterfield and Catherine Ebberts. In 1922 he married Malinda Harriet Baker. They had nine chldren, of whom two are of interest to us. The second child, Sophia Parker Butterfield, married Alexander Holland; the fifth child, Daniel Adams Butterfield, owned property just below the Payne property.

By the age of 19 he had realized his ambition to become a professional stage driver, and after diligently saving his earnings, became the owner and operator a of a livery business.

Although stern in appearance Butterfield was regarded by both partners and employees as a just and fair man. He was known as a natural leader, with an indelible memory and a generous spirit. He was a genuine 19th-century entrepreneur who relished challenging business ventures that were both profitable and served the public good.

In 1850, Butterfield convinced Henry Wells and William Fargo to consolidate their express companies with his own Butterfield & Wasson Company to form the American Express Company, which Butterfield then directed. Although the original American Express Company was primarily an express-transportation company, it is today a worldwide organization based in New York City, providing travel-related and insurance services, as well as international finance operations and banking.

In 1857, John Butterfield won a $600,000 contract to deliver the St. Louis mail to San Francisco in 25 days. This contract, the largest for land mail service that had yet been given, was awarded to Butterfield's Overland Stage Company after 9 groups had entered bids.

Originally, all groups had submitted routes that were north of Albuquerque, New Mexico territory. But the southern Postmaster General mandated that the new line be required to go through Fort Smith, Arkansas, then proceed through Texas to El Paso, onward to Fort Yuma, California and then up to San Francisco. Called the "Ox-bow Route," it added 600 miles to the original bids.

Up until this time, mail had been conveyed from East to West by private companies, some under federal contract, using various routes, including ocean steamer around South America, or overland across the Isthmus of Panama.

Butterfield immediately hired crews to prepare stations along the 2,000-mile route and water storage tanks every 30 miles, because as he said, "Remember boys, nothing on God's earth must stop the mail!"

Although Butterfield had never been west of Buffalo, New York, he decided to carry the mail himself on the first leg of the initial journey. Early on September 16, 1858, John Butterfield, wearing a yellow linen duster, a flat-brimmed hat, and pants tucked into high boots, left the St. Louis Post Office with 2 bags of mail and one passenger, Waterman L. Ormsby, a correspondent for the New York Herald.

At Tipton, Missouri 12 hours later, John Butterfield Jr. waited in a Concord Stagecoach with 4 fast horses. It took 9 minutes to transfer the 2 passengers and 2 mail bags before the coach leaped away toward Springfield.

John Butterfield Sr. rode only as far as Fort Smith, but Mr. Ormsby rode the entire 2,812-mile route through deserts, mountains, and bands of hostile Indians, all the way to San Francisco. On his arrival, he stated, "Had I not just come out over the route, I would be perfectly willing to go back, but I now know what Hell is like. I've just had 24 days of it."

The Overland Mail continued to make two trips a week for 2 1/2 years. Each Monday and Thursday morning the stagecoach would leave Tipton and San Francisco on their transcontinental journey, conveying passengers freight and up to 12,000 letters. The western fare one-way was $200, with most stages arriving at their final destination 22 days later.

While it prospered, the Butterfield Overland Stage Company employed more than 800 people and had 139 relay stations, 1800 head of stock and 250 Concord Stagecoaches in service at one time.

In March of 1860, John Butterfield was forced out, and the Butterfield Overland Stage Company was taken over by Wells, Fargo & Company due to large debts that Butterfield owed to Wells and Fargo.

With the beginning of the Civil War, the Butterfield Overland Mail discontinued the Oxbow Route; the last Overland Mail trip through the Desert Southwest was made on March 21, 1861. Wells Fargo continued to prosper with more northerly routes through mining camps, and the transcontinental railroad soon replaced the need for overland stagecoaches.

At age 59. John Butterfield retired to his home in Utica, New York, He promoted the development of telegraph lines and railroads, and in 1865 he was elected mayor of Utica. He later suffered a paralyzing stroke and died in 1869. He had established an incredible mail route, the longest in the world at the time, which provided a regular line of communication for Americans separated by almost 2,000 miles of hot, dry, rugged desert wilderness.

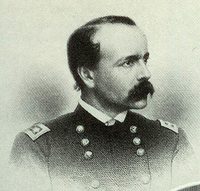

Daniel Adams Butterfield was born on October 31, 1831, in Utica, New York, the son of John Butterfield and Malinda Harriet Baker. He was the fifth of nine children. An older sister, Sophia, married Alexander Holland. After graduating from Union College, he became a businessman in New York City. When the Civil War began, he joined the Army. Although he had no Regular Army experience, he rose quickly through the military ranks. By the middle of 1861, he was a colonel of the 12th New York Militia, which he led in the Shenandoah Valley in the First Bull Run Campaign. He was appointed a brigadier general, to rank from September 7, 1861, and commanded a brigade in the V Corps/Army of the Potomac. During the Peninsular Campaign, at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, despite an injury, he seized the colors of the 3rd Pennsylvania and rallied the regiment at a critical time in the battle. Years later, he was awarded the Medal of Honor for that act of heroism.

In July of 1862, while in camp at Harrison's Landing, Virginia; Butterfield created "Taps." He began with "Tattoo," the "lights out" bugle call adapted from a French bugle call in 1835. Taking the last 5 1/4 measures of "Tattoo," he worked with bugler O. W. Norton of the 83d Pennsylvania to polish the piece into what is now known as "Taps." Butterfield himself ordered that his and Norton's bugle call be used instead of "Tattoo" to signal the extinguishing of lights in camp. After the Civil War, "Taps" would be established as the official military call for the end of the day. Butterfield also designed the system of corps badges used by the federal army. He was appointed a major general, to date from November 29, 1862. His rapid advance in the military was largely due to his skill in military administration and his well-placed political connections. Nevertheless, he returned to divisional command, after serving indifferently in the Fredericksburg Campaign. When Butterfield's friend, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, took control of the Army of the Potomac, he made Butterfield chief of staff. Butterfield soon earned the nickname, "Little Napoleon," because of his bad temper and meddlesome assertiveness. Nevertheless, Butterfield maintained his position, even after Hooker was replaced by Maj. Gen. George Meade.

Wounded during the third day of battle at Gettysburg, Butterfield took time off to recuperate. Upon his return to the army, he resumed service under Hooker at the Battle of Chattanooga. In the Atlanta Campaign, he commanded a division in the XX Corps, after which he was brevetted a brigadier and major general. Since he was sent home as an invalid before Atlanta, he finished the war on special service. After the war, Butterfield served as superintendent of the army recruiting service and colonel of the 5th Infantry, until 1870. Upon leaving the Army, he joined the American Express Company.

In West Park, he was active in the Church of the Ascension. After the death of his wife, he had the interior of the Church redecorated as a memorial to her and their only child. In 1886 he remarried in St. Margaret's Church in London. It seems that he did not spend time at West Park thereafter, and he settled at Cold Spring, New York, where he died on July 17, 1901 He was buried at West Point by special order, although he never attended the military academy.

Marist University | Marist Archives & Special Collections | Contact Us | Acknowledgements