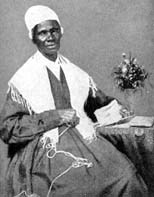

Sojourner Truth, a Slave who Grew up in West Park

Sojourner Truth is rarely mentioned in the histories of Ulster County. Her story highlights an unflattering underside of the growth of the county, viz. the reliance on slave and indentured servant labor. The Dutch and Portuguese were the principal slave traders from Africa, and by 1800 New York was the northern state with the most slaves. Important Dutch-origin persons in Ulster, Kings and Richmond headed the opposition to abolition of slavery in New York. To be fair, a statue of Sojourner Truth stands near the county office building in Kingston.

Northern slavery was substantially different from that in the South, where large groups of slaves were kept on large plantations. In the North, slaves rarely numbered more than four or five in any family.

Isabella was born in either Rosendale or Tillson sometime between 1795 and 1799, the most probable date being 1797. Written records were not kept of the birth, marriage or death of slaves. Most of what we know about Isabella's childhood comes from her Narrative dictated to Olive Gilbert around 1850, but what few other sources we have seem to corroborate that testimony.

Isabella was born to James (born circa 1760) and Elizabeth "Betsy" (born circa 1770), two slaves who may have come from Africa, but at the time of Isabella's birth belonged to Johannis Hardenbergh, of the family associated with the Hardenbergh Patent. James was tall and had the nickname Bomefree, meaning "tall tree"; Betsy was called Mau Mau, a Dutch term for "mother". The couple had about thirteen children, most of whom were sold away or donated to other members of the Hardenbergh family. James and Betsy were favored by Johannis Hardenberg with a separate cabin, but when Johannis died and his son Charles inherited Hardenberg Hall and the farm, the couple and their remaining children were moved back into the main house, in the damp, unheated cellar, lit only by a small window.

Isabella's mother carried out a common tradition for peoples who could neither read nor write; she told her daughter stories of her older sisters and brothers. In particular, she told Isabella how a five year old boy and his three year old sister were grabbed, loaded into the Hardenbergh carriage, and taken away to other owners. Isabella was too young to know these two, but later in life she encountered the boy in New York City, her sister having died just a few years before the encounter. Isabella remembers receiving beatings from the master, but thought they were probably deserved. Such slave beatings were common even for young children,

After the death of Charles Hardenbergh, around 1807, Isabella was sold to the Neely family for $100. The Neelys spoke only English, and Isabella spoke only Dutch, so communication was difficult. Isabella received beatings which left welts and scars on her back for the rest of her life. In about a year, she was sold to the Schriver family. Mr Schriver was a pillar of the Klyne Esopus Dutch Reformed Church, but he also ran a tavern, where Isabella learned to swear and smoke.

In 1810, she was sold for $175 to John J. Dumont and his wife Sally, who occupied over 770 acres of land in river lot #9 of the New Paltz Patent, about 1600 feet south of the Payne lands. She stayed with the Dumonts almost seventeen years. John Dumont praised her work, maintaining that she could outperform any of his male slaves or servants. Sally complained that Isabella got all that work done because she did it poorly. The other slaves were unhappy with Isabella, for they found no reason for industry -- there was no incentive.

Isabella had a simple romance with a slave from another property, but that slave's owner caught them on the Dumont land and whipped the young man soundly. She was then married to James, who had been married twice previously. It is probably that James' first two wives were sold to others, as slave marriages were not considered important. Isabella had five or six children, that remained on the Dumont land.

Massachusetts, Connecticut and Pennsylvania abolished slavery soon after the Revolutionary War. while the move to abolish slavery was slow in New York State. The landowners opposed abolition because they saw it as a loss of labor. Finally a compromise was reached in 1817. Any slave born before 1799 had to be released by July 4, 1827. Slaves born after that date could be kept as slaves until 28 years old if male, and 25 years if female. (Isabella probably had five children between 1815 and 1826; Diana, born about 1815; Peter 1821; Elizabeth 1825, and Sophia, 1826. The fifth perhaps named Thomas, may have died in infancy, and probably came between Diana and Peter. This meant that Diana would remain a slave until 1840, Peter to 1849, Elizabeth 1850 and Sophia 1851).

Masters could free their slaves earlier. However, if they freed them after the age of 50, they had to post a bond of $200 for their upkeep in the poorhouse. The pattern developed to free those slaves who had lost their capacity for full labor before the age of 50, when the bond was unnecessary. This happened to James and Betsy. Like many others, they lived in the woods, hoping for some charitable shelter during the harsh winters. Betsy died about 1809. James lingered on a few years after, blind and lame. Isabella saw him once more, but learned of his death only after the fact.

John Dumont promised Isabella that he would free her a year before the deadline. However, Isabella injured her hand which left it deformed, so John unilaterally decided that she should stay the entire term. After the agreed earlier date passed, he gave her about 100 pounds of wool to be woven, which she did at night after her normal chores. This took about six months. Isabella then decided that she had done enough. Just before dawn, she set out with her youngest child and a kerchief of clothes, and walked to the house of Levi Rowe, an old friend, whom she found on his deathbed. He directed her to the home of Isaac and Maria van Wagenen, who took her in. Later that morning, John Dumont arrived to take her back. The van Wagenen's paid Dumont $25, amounting to $20 for a year's work of Isabella, and $5 for the child. Isabella took their name (often spelled van Wagener) and stayed with them for about a year. It was common practice for a slave to take his/her master's last name when freed; taking van Wagener rather than Dumont showed her appreciation of Isaac and Maria.

A common trick was to sell off slaves to states in which slavery was legal after 1827, even though this was subject to severe penalties: 14 years in prison and $600 fine. Towards the end of her stay in Ulster, Isabella learned that her son Peter had been sent to Alabama. Dumont had sold Peter to a Dr. Gedney in 1826 who intended to bring him to England, but he found Peter too young to carry out any of the envisioned duties. Dr. Gedney in turn sold him to his brother, Solomon Gedney, who gave Peter to his daughter, who had married a Fowler from Alabama. Peter was taken with the new bride to Alabama. When Isabella discovered this, she was not content to shrug it off. After pleading with the Dumonts ( the Gedneys were related to Sally), Isabella walked to Kingston and visited a lawyer, who told her he would get Peter back in 24 hours if she gave him $5. Isabella walked about 12 miles to ask a Quaker group for the money; she then returned to Kingston and gave the lawyer the money. Since the young man had already been sent to Alabama, it took several months to retrieve him. The boy was brought before a judge, together with Isabella and Fowler. At first the boy denied that Isabella was his mother, but the judge awarded him to Isabella. When it became clear that Peter would stay with Isabella, he admitted that he had been severely beaten by Fowler, and Isabella saw the welts and open wounds on his back. A few years afterwards, Fowler struck his wife in a fit of anger, killing her. He was imprisoned, and their children were send north to the Gedneys.

During Isabella's years in Ulster, she became involved with the Methodist Church, but also believed that she had direct communication with God. The Methodists group she associated with were part of the perfectionist movement (today we would call them Pentecostals). Many of the meetings were spontaneous, and Isabella found she had a gift for speaking or preaching.

About 1828, Isabella sensed that God told her to move to a larger audience. She took her son (who had been freed because of the Alabama episode) and moved to New York City. She lived on Bowery Hill with the family of James Latourette, a furrier with a shop on Canal Street, who was also a Pentecostal. Mrs. Latourette was a member of a group of women who ventured into Five Points to help out. Isabella got caught up in several movements, once with the Prophet Matthias, later with the Millerite groups. Matthias grew up on a farm in Washington County and decided he was the second coming. Coincidentally Miller grew up on Washington County near Glens Falls. His careful reading of the Bible led him to discover that the second coming would occur sometime between 21 March 1843 and 21 March 1844. Later in life Isabella would deny she was a Millerite, but she certainly participated in many of the camp meetings.

Peter became a discipline problem, and eventually was given the choice of prison or shipping out on a whaling ship. He chose the latter, and there are several letters he wrote or dictated while on the ship. But we have no record of what happened to him.

Despite the falling out between Isabella and Dumont, she returned to Ulster to care for the dying Sally Dumont. John Dumont left Ulster for Dutchess County in 1849, and brought Elizabeth and Sophia with him After this, Isabella did not return to Ulster.

In 1843, Isabella decided she ought to leave New York. She now called herself Sojourner Truth, indicating that she felt she ought to be itinerant but always tell the truth about the Lord. She traveled east to Long Island, where she enjoyed the hospitality of Millerite families and participated in their camp meetings. She then took the ferry to Bridgeport, and traveled up the Connecticut River through Hartford, Chicopee and Springfield. When Fall arrived, she looked for a place to stay the winter. She found it in Northampton.

About this time there were many groups which formed separate communities based on utopian principles, among them Brook Farm and Hope Farm. Several of these were in Massachusetts. A common trait was denial of the usual priestly formats of religion, relying on direct communication between the person and God. The Northampton Association of Education and Industry was led by William Lloyd Garrison's brother-in-law. In 1841 the group purchased a bankrupt Northampton Silk Company along the Mill River. The property included a large four-story brick factory building 120 by 40 feet on 420 acres of land along the Mill River. In its heyday in 1845 the group numbered 210 members, mostly from Massachusetts and Connecticut. It followed egalitarian principles, treating equally men and women, black and white, which impressed its members and visitors.

Through this group Isabella was introduced to a great number of abolitionist persons. In addition, she was introduced to Olive Gilbert, a woman who became Isabella's amanuensis, writing Sojourner's story as a narrative, completing it about 1850. Sojourner lived for a time with the Bensons, then purchased one of the houses on the mill property, undertaking a mortgage commitment which lasted many years. She hoped to sell her Narrative at meetings when she preached; this took a long time, as she only charged 25 cents per narrative.

There are plenty of accounts of Sojourner's later life. She gravitated to Washington DC during the Civil War, where she tried to work the camps of the freed slaves in and around the city. Later, she relocated to Battle Creek, Michigan, selling her Northampton house and purchasing another. She remained very active in the abolition movement, which transmuted into the issue of voting for blacks. Many of the abolitionists wished to downplay the parallel issue of voting rights for women. Sojourner insisted that the issues were not divisible. Her imposing personality and entertaining method of presentation kept her a popular speaker until shortly before her death in 1883.

While at Battle Creek, three of her daughters lived with or near Sojourner. Neither she nor her daughters ever learned to read or write, nor did they profit financially from Sojourner's fame. Elizabeth Boyd died at home of "nervous prostration" in June 1883; Sophia Schulyer died in the county poorhouse of "old age" in March 1901; and Diana Corbin died of chronic ill health in the county poorhouse after being an object of private charity for ten years.

Sojourner's fame spread slowly by means of her Narrative. She asked William Lloyd Garrison to write something about it in the preface. But her fame spread quickly when Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote about Sojourner in the Atlantic Monthly in 1863. Unfortunately, Stowe's work contains many errors, which simply did not go away as other writers used Stowe as a source. About the same year Frances Gage, who had chaired the 1851 Ohio Women's Rights Convention which catapulted Truth to national fame, wrote an account of Sojourner's speech. The twelve years between Truth's speech and Gages account gave room for lots of 'poetic license'. There is a short account of Truth's speech written soon after by the secretary of the Convention, which differs substantially from Gage's account. The ideas of Stowe and Gage remained dominant until the middle of the twentieth century. In the past five decades more attention was paid to the historical aspects. Unfortunately Sojourner's influence came from her speeches and preaching; there is nothing which she herself wrote, and her manner of speaking was considered unique and entertaining.

References:

Margaret Washington, Narrative of Sojourner Truth, An authoritative, annotated edition of a landmark in the literature of African-American women. Edited and with an introduction by Margaret Washington, Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, Inc. New York, 1993, 138 pp. The introduction authored by Margaret Washington gives a concise view of Northern slavery, and slavery in Ulster in particular.

Nell Irvin Painter, Sojourner Truth, A Life, A Symbol, New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 1996, 370 pp "This vividly imagined and forcefully written portrait of the iconographic Sojourner Truth is one of the finest biographies of recent years. In her dual roles of historian and cultural critic, Nell Painter is brilliant." --- Joyce Carol Oates Nell Painter separates the history of Truth from the legend as far as possible, and points out how the erroneous information became part of the legend.

Marist University | Marist Archives & Special Collections | Contact Us | Acknowledgements