Esopus Grounds and Buildings

The grounds of Marist Preparatory School described by Brother Francis Xavier in 1942

November 1942

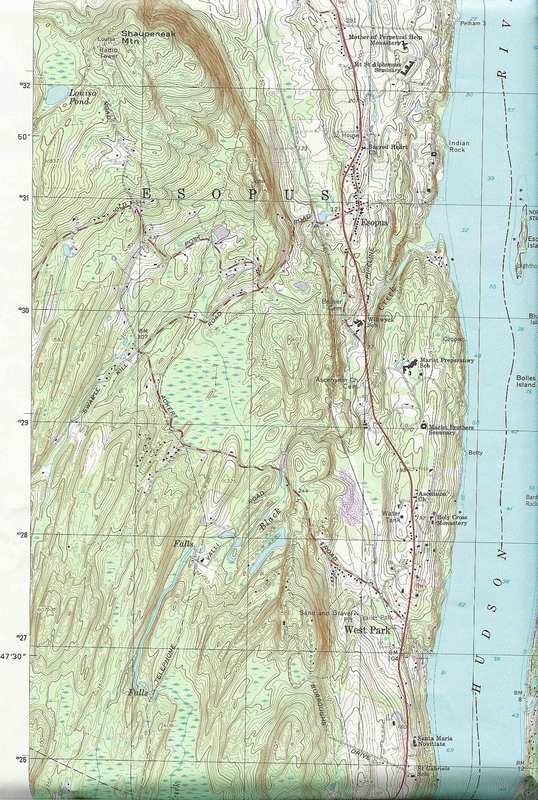

The Marist Preparatory School property which was acquired during the past summer is a two hundred acre plot of land, located in part in the village of West Park and in part in the town of Esopus, and bounded on the west by route 9-W (also known as the Albany Post Road), and on the east by the Hudson River. This piece of land was detached from a much larger estate of approximately 800 acres which had been assembled by the late Colonel Oliver Hazard Payne during the early years of this century. This was later willed by him to his favorite nephew, Harry Payne Bingham, who donated it outright to the New York Protestant Episcopal diocese which transformed it into a convalescent home operated on a charity basis.

Due to the windings of the highway and to the irregular indentations caused by the river, the lot assumes a shape which in no wise resembles any definable geometrical figure. It runs over four thousand feet in a rather broken line along route 9-W and skirts the Hudson shore three thousand four hundred feet as the crow flies. The southern limit is roughly 1/4 of a mile and the northern extremity goes well beyond a mile in its greatest length.

Since this territory lies within the range of the Shawangunk mountains, the surface of the property is rather uneven. A central plateau of comparatively uniform altitude runs from north to south and takes in a great part of the acreage. On the east the land slopes very rapidly away from the central height of land to the shores of the Hudson. On the west the steepness is less pronounced except at the northwestern extremity of the estate where the greatest contrast in levels and the sharpest declivities are found. The architects who planned the arrangement of the buildings very wisely placed all the dwelling houses on the central plateau, thus facilitating communication, drainage, and distribution of water supply.

A complex system of wide, well-built roads reaches to practically all sections of the property. These roads vary in width from twenty-five foot main arteries to ten or twelve foot driveways in the more remote and less frequented portions of the grounds. Most of these roads are lined with stately shade trees (mostly maples and elms) thus forming pleasantly secluded walks. Without any definite data as yet available, it seems safe to assume that the mileage of roadways on the estate totals somewhere between four and five miles. A very complete and carefully planned system of drainage, both at the surface and underground, takes care of rain water and prevents costly erosion. Considering the number of years that the grounds, have been left without proper care, since 1927, the roads and the system of drainage are in a surprisingly excellent state of preservation which is unquestionable evidence of the quality of the original workmanship.

A previous reference to the location of this property in mountain country may have created an impression of enormous rocks and precipitous ledges breaking out at the surface in the most undesirable places. This was undoubtedly the case at the time the land was in its natural condition. But long years of terracing, landscaping, and importing of the highest grade of top soil, accompanied by scientific fertilizing and loaming, have given the property -- at least that portion which is not totally wooded -- a top dressing which hardly, could be surpassed in quality. Lawns, gardens, and orchards have occupied large tracts of the grounds in the past and there is no good reason to suppose that they could not do just as well in the future. As one approaches the shores of the Hudson, in the steeper and more hilly portions of the woodland, the typical bluestone and shale common to the region become as evident as in other sections of eastern New York.

The intelligent care which was exhibited in the landscaping of the property was still further manifested in the attention bestowed on the woods and groves. The evidence of an expert's, guidance in the choice, the grouping and the training of the trees and bushes is apparent even to the most casual of observers. Effectiveness was not obtained by sacrificing the natural to the artistic. It was rather a case of improving what was already beautiful and pleasing. While one grove is intended to present a similarity in foliage, another strives to bring out a contrast in coloration.

Some clumps of maples bring together as many as eight variations of this prolific family, and neighboring collections of evergreens exhibit surprising varieties of conifers. Bushes and vines, flowering and non-flowering, have been scattered about with a prodigality which was restrained solely by the rules of good taste. One need not be a trained botanist to appreciate the wonders of native and imported plant life which are found in even the most unexpected parts of the woods.

It is difficult to estimate from mere inspection the amount of land actually fully wooded and the proportion which is cleared of trees and brush. A great part of the central plateau is either open ground or fields with occasional groups of trees and bushes thrown about to relieve the monotony of interminable green lawns. Much of the sloping area along the old Post Road has likewise been opened and landscaped. The total acreage devoted to open fields or lawns probably comes close to one hundred acres. The greater part of this was at one time kept up as regularly cut lawns and even today it would not require too great an expense of time and labor to bring back much of this to the trim condition of former days. From the front of the Mansion, looking towards the river, one sees a terraced slope two thousand feet long which still conjures imaginings of a green carpet extending to the water's edge. It is claimed that during the lifetime of Colonel Payne sixty acres of the estate were maintained as close cropped lawns.

Passing from the foregoing summary inspection of the ground, to a brief examination of the buildings, it is advisable to consider these as subdivided into two groups: those built of white limestone, native or imported, and those constructed of blue limestone quarried on the estate.

The gatehouse, a classical two-story structure of somewhat sober Italian Renaissance style, logically deserves first consideration due to its location at the main entrance of the grounds, the vehicular gateway facing route 9-W. A curving ten-foot wall, also of white limestone, which leads up to a massive grilled iron portal, recessed one hundred fifty feet from the line of the highway, bears out still further the suggestion of a Florentine villa of the fifteenth century.

One thousand feet further into the property, having negotiated the climb which winds to the level of the central plateau, one comes upon a French chateau, with towered keep, dormer windows, and many-gabled red-tiled roof, a replica of seigniorial residences in the land of Provence. This was the gardener's cottage. Living quarters were on the second and third floors. The spaciousness of the rambling ground floor was subdivided into large, white-tiled halls which housed the indoor activities of the florists and gardeners. At the rear of this cottage, and directly connecting with it, with its long axis laid out in an easterly direction, is the greenhouse. This was once a proud, glass-domed structure of great beauty. but the challenge of so much unprotected glass was too irresistible for the youth of the neighborhood. Ruins, all the more ghastly because of the evident past grandeur, are all that is left of the splendor of better days. The east end of this terminates in a white limestone two-story tool shed, which balances to a degree the cottage at the opposite end.

December 1942

Two hundred feet further, the main road runs into a T-Shaped intersection, with the upper bar of the T running north and south. A two-minute walk towards the south brings one to the principal building on the property, the Mansion. The first impression is of of vastness and solidity. Closer inspection causes a definite sense of deception. The entrance lacks the pretentiousness which might be expected from the general proportions of the building. But the fact really is that this is simply a side entrance, an opening for the purposes of every day usage, a mere door for the convenience of the general public.

The front of the mansion is to the east overlooking the Hudson River. A beautiful colonnade of fifteen-foot white limestone columns supports an artistically decorated roof of the same material which shelters a marble porch running the length of the building. Seven French windows, set in archways seven feet by fifteen, lead from this porch into what was once the grand reception room of the former owners. This is now a beautiful chapel, which is characterized by a marked liturgical simplicity. The high vaulted Dutch gold ceiling, the sculptured marble archways, the hand carved oak pilasters which separate the sections of paneling, the antique red-tiled floor with its offsetting multicolored marble border are just a few noteworthy features of a room which is every way remarkable.

As might be expected, the other rooms on this floor are in keeping with the reception room. The library is conspicuous for its mahogany beamed ceiling and its wall trimming which frames rich brown leather panels. The mahogany hand-carved insets over the doors and windows as well as the massive ceiling cornice, arrest the attention in the dining room which is completely finished Circassion walnut. A brightly colored ceiling ornamented with well-preserved gold filigree work calls for special notice in the breakfast room. And the view of the Hudson river which one gets from the lounging room is both unusual and surprising. No description these rooms would do justice to the subject without some mention of the artistic fireplaces, each of a unique design executed in special color of marble.

The ascent to the second floor, the private room floor, is by means of a white Carrara marble stairway. The ceiling of each bedroom is worked out in ornamental plaster, the walls are silk lined, the woodwork is solid oak finished in white enamel, each floor is parquetted in a design all its own. Here again there are Tiffany styled marble fireplaces which offer a variety of colors and method of execution. Spacious bathrooms with walls and floors of marble connect with most of the bedrooms.

The house is laid out as a hollow square arranged around a central patio, the hallways being along the inner walls of the building. Three of the wings open directly into the interior court through plate glass doors which are protected by a grille of wrought iron. These doors lead to recessed porches whose roofs are supported by columns of white limestone. The court is sixty feet by sixty. The center piece of this area is a fountain surrounded by a large basin. Forming the base of the fountain and supporting it several feet higher than the basin is a genuine antique statue of Atlas pictured in his traditional posture with one knee on the ground.

Heroic sized murals, based on mythological themes, occupy, the space over the doors in the three recessed porches which lead from the building to the patio. The contrast in colors created by the blue background of these paintings is meant to set off the while limestone columns which might otherwise be lost in the general whiteness of the building.

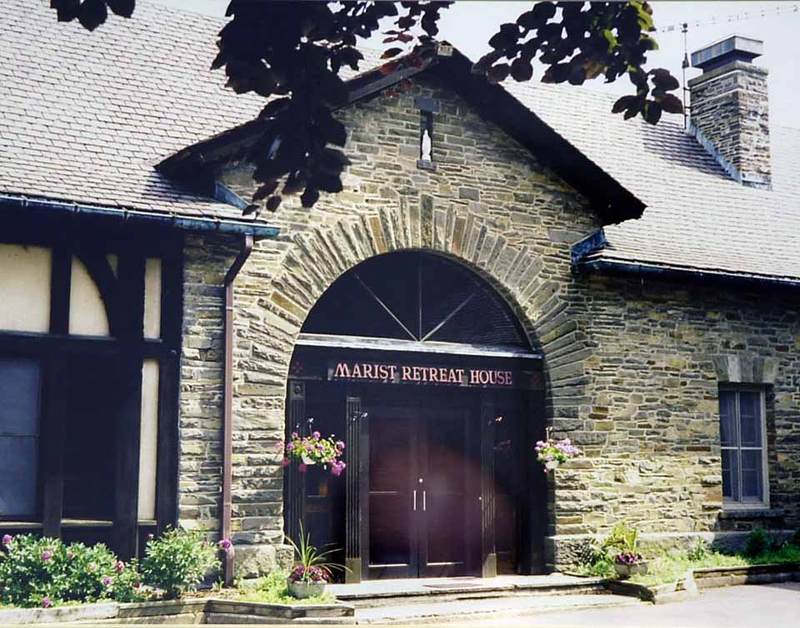

So much for the constructions of white limestone. Lying to the north of the mansion, and roughly three-tenths of a mile from it, is a large group of buildings consisting of a cottage and several service structures. These are of blue limestone. The houses arc arranged around a partially enclosed area, very much in the form of a deep U.

These squat, ivy-covered, grey buildings with their high sloping roofs of blue slate, characteristic slender chimney pots, low windows, octagonal north tower are decidedly English in every detail of their architecture. The high stone wall which closes the open end of the U recalls the necessity under which each large English household was placed to protect itself against the surprise attacks of the gentry who wore Lincoln Green. Stately elms scattered over the lawns which border the roads within this group add to the suggestion of an England of yesteryears.

A scant minute's walk from these buildings, and directly to the east of them, is another cottage of the blue limestone variety. This was formerly the residence of the superintendent of the estate. This is the oldest house on the estate and is the only relic of the days when part of this land was owned by the Astors [ed note should be Pratts], long before the beginning of this century. In spite of its age it is still in a very good state of preservation. The former Episcopal owners made it serve as a sort of dining pavilion for their convalescents. Two large annexes were added by them in order to accommodate more people at one sitting. It is a very roomy building and could take care of a good

Other buildings on the property are: a large ice house, located at the northern extremity of the pond which is near the center of the estate, and strictly speaking an appendage of the English group; a fortress-like coalhouse on the shores of the Hudson, where twelve hundred tons of coal could be unloaded from barges at one time; a small pumping station, very close to the northeastern corner of the property, and along the river's edge, which houses pumps and other machinery connected with the water supply of the place; finally, a boat house, practically at the southeast corner of the grounds. An extra word about this latter building might be in order.

One of Colonel Payne's hobbies, possibly his only one, was yachting. During the later years of his life, he became the owner of the largest, fastest, best appointed steam yacht then afloat, the "Aphrodite". The operation of this immense boat -- it was over three hundred feet long -- required an unusually lengthy docking space, affording a depth of water sufficient for a craft of that tonnage. So, at the southern extremity of his estate, directly in the line of vision of his mansion, the Colonel had a dock built of reinforced masonry which extended far enough into the channel to guarantee a minimum depth of twenty-five feet of water at all times. This shell was then filled with rocks and the surface was leveled off with earth. Today, this large artificial platform is still intact and affords an ideal place for fishing, diving, swimming and picnicking. The boat house is built at the northern extremity of the dock and encloses a basin, large enough in length, width and depth to shelter fully quite a large tender or dinghy of a larger boat. This was exactly the reason for which this structure was erected, to provide a safe anchorage for the small boat of the "Aphrodite" when the latter was at its Hudson anchorage. At the opposite end of the dock is a Pavilion built entirely of cut stone and roofed over with red tiles.

All the buildings described in this article are steel and concrete structures and therefore fully fireproof, with the exception of the superintendent's cottage and the cottage in the English Village which are rated semi-fireproof.

This essay appeared in the September and December 1942 issues of the Marist Brothers' publication Bulletin of Studies, available in the Marist Brothers' archives in Esopus.

Marist University | Marist Archives & Special Collections | Contact Us | Acknowledgements