Cornell's Influence on Washington Rowing - Family Version 8-6-16.pdf

Media

- content

-

Revised 8 - 6 - 16

CORNELL’S INFLUENCE ON WASHINGTON ROWING

:

MARK ODELL IN NEW YORK, THE KLONDIKE, AND SEATTLE

By John W. Lundin and Stephen J. Lundin, Seattle Wa.,

Copyright 2021

John@johnwlundin.com

,

s.lundin@comcast.net

John took advantage of the contributions of his grandfather (Mark Odell, Cornell 1897) to

Washington rowing, and rows out of the Pocock Rowing Center in Seattle with a club that uses the

classic Thames watermen’s stroke taught by George Pocock.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

CHAPTER I: ODELL FAMILY HISTORY

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

CHAPTER II: ROWING AT CORNELL UNDER COACH COURTNEY:

1897 IRA WIN BEGINS A ROWING DYNASTY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .25

A. EARLY DAYS OF ROWING AT CORNELL . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

B. 1883 - CHARLES COURTNEY BEGINS COACHING CORNELL CREWS. . 28

C. ODELL’S ROWING EXPERIENCES AT CORNELL: 1893 - 1898. . . . . . . . . . 37

D. CORNELL FINALLY ARRANGES TO ROW AGAINST YALE &

HARVARD IN 1897

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

E. ODELL’S CORNELL CREW OF 1897 BEATS YALE AND HARVARD,

ESTABLISHING CORNELL AS A ROWING POWER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .55

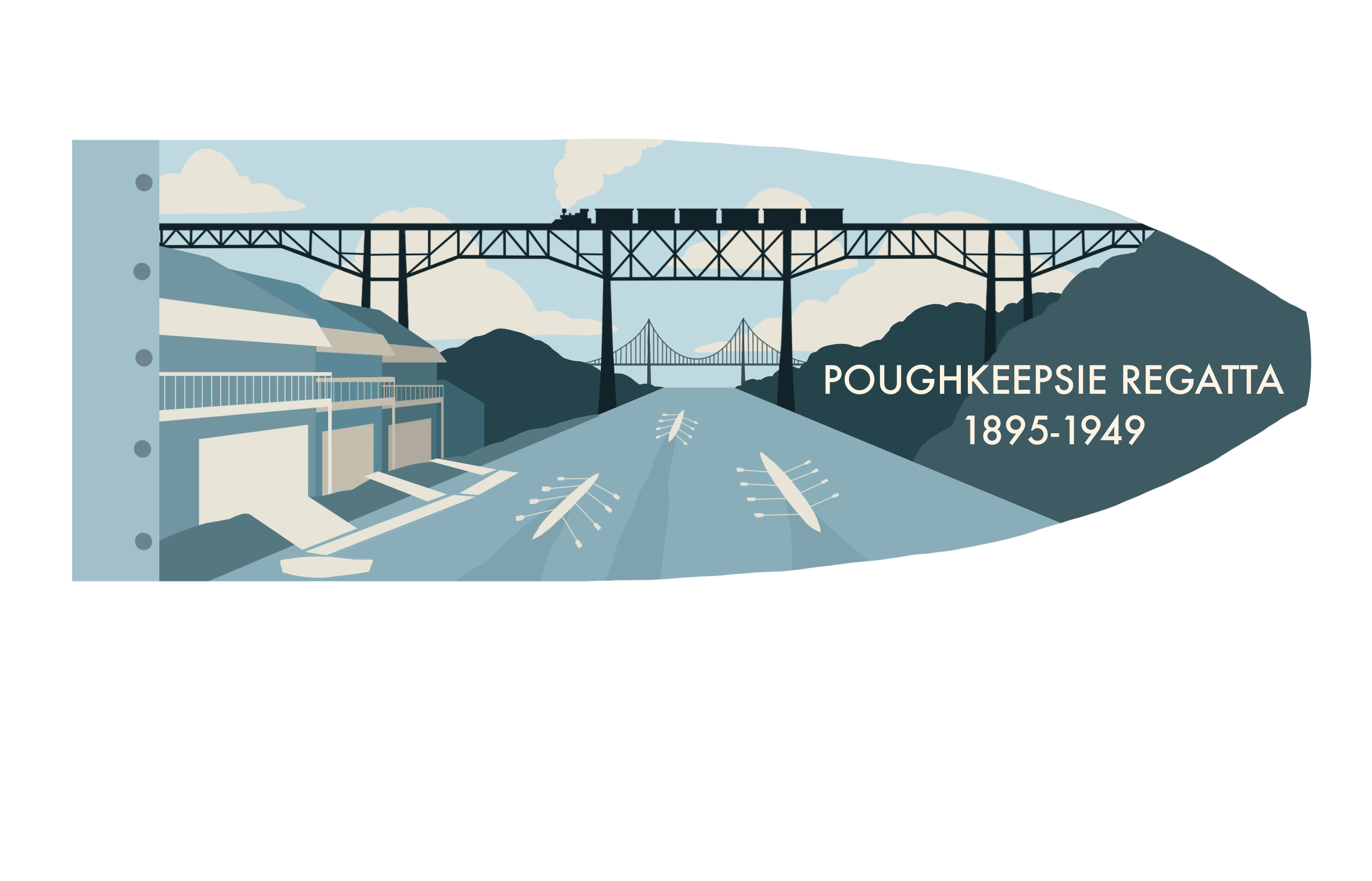

F. CORNELL ROWS IN SECOND EVENT AT POUGHKEEPSIE

- THE IRA REGATTA AGAINST COLUMBIA & PENNSYLVANIA. . . . . . . . .87

G. THE “COURTNEY STROKE” WON THE RACE

S

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .95

H. ACCLAIM FOR THE CREW OF 1897 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .101

I. COURTNEY AND CORNELL ROWING AFTER 1897 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .111

CHAPTER III:

LEAVING THE IVY LEAGUE FOR THE WEST:

GOING TO THE KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH VIA SEATTLE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .113

A. ODELL ATTENDS CORNELL LAW SCHOOL FOR THE

1897 - 1898 TERM BUT CATCHES GOLD FEVER. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .113

B. 1898: KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH ENDS THE SILVER DEPRESSION. . . . . .117

C. ODELL LEAVES CORNELL FOR THE KLONDIKE GOLD RUSH. . . . . . . .133

D. SKAGWAY TO DYEA & OVER CHILKOOT PASS

.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146

E. CHILKOOT PASS TO LAKE BENNETT. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167

Page -a-

F. VOYAGE DOWN THE YUKON RIVER TO FORT SELKIRK. . . . . . . . . . . . .191

G. PROSPECTING NEAR FORT SELKIRK. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 214

H. DREAMS OF GOLD RUSH RICHES FADE: LEAVING THE

YUKON FOR SEATTLE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 232

CHAPTER IV: MARK ODELL MOVES TO SEATTLE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 245

A. ODELL LEAVES THE GOLD RUSH FOR A NEW LIFE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .245

B. SEATTLE IS FOREVER CHANGED BY THE GOLD RUSH. . . . . . . . . . . . . 247

C. ODELL GOES TO WORK IN THE THRIVING CITY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 253

D. 1911 - ODELL STARTS HIS OWN COMPANY & GETS MARRIED. .. . . . . .273

E. 1916 - ODELL RETURNS TO SEATTLE AND CONTINUES HIS

CONSTRUCTION WORK . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 288

F. 1930s - ODELL CHILDREN ATTEND COLLEGE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 297

CHAPTER V: ROWING STARTS AT WASHINGTON WITH CORNELL’S

INFLUENCE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .336

A. THE EARLY DAYS - ODELL BECOMES COACH IN 1906. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 336

B. THE CONIBEAR - POCOCK ERA. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 338

C. THE CONIBEAR STROKE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .357

D. WASHINGTON BECOMES A ROWING DYNASTY AND

INFLUENCES ROWING THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY. . . . . . . . . . . . 369

REFERENCE MATERIALS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .385

Page -b-

INTRODUCTION

Cornell made a major contribution to rowing at the University of Washington and the entire

west coast, a story not well known in Ithaca or in Seattle. Mark Odell, the authors’ grandfather,

rowed on Cornell’s national championship crew of 1897, coached the University of Washington

crew in Seattle in 1906, and assisted Washington’s famous coach Hiram Conibear after he was hired

as Washington’s crew coach in 1907, since Conibear did not know how to row. Odell taught

Conibear and Washington rowers the Courtney stroke he had learned at Cornell, which was later

known as the Conibear stroke as Conibear and Washington rowers influenced rowing around the

country.

Mark Odell, who was born and raised near Baldwinsville, New York, rowed for Coach

Courtney on Cornell’s famous crew of 1897, which was finally able to row against Yale and Harvard

for the first time in two decades. To everyone’s surprise, and contrary to the predictions of the

rowing experts, the Big Red crew of 1897, won the Intercollegiate Rowing Association (IRA)

Regatta on the Hudson River at Poughkeepsie, New York, and became “champions of America.”

New York Journal

, June 25, 1897. Cornell beat heavily favored Yale and Harvard, establishing the

school as a rowing power and Charles E. Courtney as the leading rowing coach in the country.

Cornell crews, under the guidance of Coach Courtney, dominated college rowing for two decades

thereafter.

In March of 1898, Odell dropped out of Cornell Law School and with his best friend from

school, Ellis Aldrich, went to the Klondike Gold Rush in 1898, where he spent nearly a year

prospecting for gold under harsh conditions. The following is Odell’s itinerary in the Klondike.

March 2, 1898 – Aldrich suggests going to Klondike gold rush

Page -1-

March 16 – Odell and Aldrich leave New York for Seattle

March 21 to April 3 – travel from Seattle to Skagway, Alaska

April 8 to 14 – move supplies from Dyea to Chilkoot Pass Summit (CP)

April 15 to May 14 – move supplies from CP Summit to Lake Bennett

May 20 to June 22 – make boat for Yukon River travel

June 23 to July 26 – travel on Yukon River from Lake Bennett to Ft. Selkirk

August 2 to August 13 – prospect at Wolverine Creek (WC)

August 20 to August 30 – re-supply for winter at WC

August 30 to February 1899 – prospect at WC

February 15 to March 8, 1899 – travel from Ft. Selkirk to Skagway

March to December 1899 – work in Skagway

December 1899 – move to Seattle

1

Odell moved to Seattle in 1899, where he raised a family and became a contractor and

helped to build that growing city’s infrastructure. The Odells were one of Seattle’s prominent

families, often in the news.

Peter Mallory, who wrote the seminal book,

The Sport of Rowing, Two

1

In 1960, in a letter written to a relative, Odell described his time in the Yukon in his

typical modest way:

“March, 1898, left with my college chum Ellis L. Aldrich for the Klondike via Chilkoot

Pass, Miles Canyon, Windy Arm, White Horse Rapids, Five Fingers Rapids, Squaw

Rapids, and the like, building our boat with raw lumber from green trees on Lake Bennett

near the source of the Yukon River, loading it with a year’s supplies bought in Seattle,

brought over the pass in many, many pack loads and then sled loads to our camp on Lake

Bennett. All we would need to eat, wear, and use for a year, a requirement of the

Canadian Police stationed at the Alaska-Canada border line. In our case about a ton and

a half. A year of wonderful adventure and experiences. But remember - there were

thousands upon thousands of people who did this in 1897 and 1898. In Seattle, above

tale is commonplace.”

Page -2-

nturies of Competition

, has carefully analyzed the Conibear Stroke, and has determined its genesis

and Cornell’s influence on it.

Many have described George Pocock as the sole author of the Conibear Stroke, but history

demonstrates that this is less than the full story. Conibear

?

s descriptions of the ideal stroke

differed substantially from George Pocock

?

s written descriptions of the Thames Waterman

?

s

Stroke. It would be more accurate to recognize that the Conibear Stroke was the result of

crucial early consultation with

Charles Courtney

reinforced by having former Cornell rower

Mark Odell

as a volunteer assistant in Washington program. Add in the influence of George

Pocock, and Conibear had everything he needed to supplement his own innate intelligence.”

(Emphasis added)

2

Washington, in turn, after getting its start as a rowing power with Cornell’s help, sent

coaches schooled in its rowing techniques all over the country to develop crew programs at many

different universities, including a Washington rower who went to Cornell. Rollin Harrison “Stork”

Sanford (U.W. ‘26) was hired as Cornell’s coach in 1937, and coached there for 34 seasons, winning

six IRA championships.

An article in the Cornell Sun of April 23, 1926,

College Rowing Influenced by West’s

Methods,

described the influence of Washington trained coaches at Eastern schools.

College rowing not only hold forth prospects of unusually keen competition in the East this

spring, but will be featured simultaneously by introduction of the so-called “Washington

system” on a scale as wide-spread as it is interesting.

No less than four major Eastern institutions will have products of the University of

Washington school as head coaches of their oarsmen this season. The most conspicuous, Ed

Leader, of Yale, begins his fourth year at the helm of the Eli rowing with an unbroken record

of varsity victory. Pennsylvania, Princeton, and the Naval Academy have turned their rowing

destinies over to graduates of this new Far Western cradle of oarsmanship for the first time.

It was three years ago that Leader’s initial success forced the East to sit up and notice this

owing dynasty, founded by Hiram Conibear less than twenty years ago at Washington, and

2

Mallory,

The Sport of Rowing, Two Centuries of Competition

, to be published in the fall of

2011

,

page 423.

Page -3-

developed to its present fame within less than a decade. While Leader was turning out

Olympic champions at Yale, his alma mater’s success in developing victorious crews under

“Rusty” Callow attracted almost equal attention.

These two factors combined, apparently, to convince Eastern rowing authorities that the

“Washington system” is sycomorus with triumph on the water. At the same time the spread

of this system has been due not only to the fact that Washington had been turning out crews

which have finished first twice and second twice at Poughkeepsie in the last four years, but

to the production of oarsmen capable of imparting their knowledge of this picturesque sport.

It is a coincidence that the Naval Academy, whose varsity crews have been the only ones to

defeat Washington at Poughkeepsie in the last four years, selected Bob Butler, a Washington

graduate, as its head coach for 1926 after differences which resulted in the departure of the

famous Glendons, “Young Dick” and “Old Dick” from Annapolis to Columbia. Chuck

Logg, at Princeton, and Fred Spuhn, at Pennsylvania, are the other new head coaches of the

Washington school...

In the face of this new influx of coaching blood and system, Jim Ten Eyck, Syracuse’s

“Grand Old Man” remains the only survivor of the famous school which also included “Pop”

Courtney, of Cornell, Jim Rice, of Columbia, and Joe Wright of Pennsylvania.

Page -4-

CHAPTER ONE

ODELL FAMILY HISTORY

Our grandfather, Mark Odell, was born on January 13, 1869, on his family’s farm outside of

Baldwinsville, in upstate New York, 12 miles up the Seneca River above Syracuse, to Benjamin

Bradford Odell, Jr., and Mary Augusta Betts Odell.

Odell Family in England

The Odells are an old English family from the county of Bedsfordshire, dating to the time

of William the Conqueror, and were early settlers in what later became the United States,

immigrating originally in the 1600s. There is lot of information about the history of the Odell

family available on line, although some of the accounts are in conflict with each other. The

following is taken from those sources.

3

Odell is an Anglo-Saxton name of great antiquity in England. The name Odell was

established when the original families resided in a village called Wadelle or Woodhill (later known

as Odell), in Bedsfordshire, located in the east of England, north of London, bordered on the north

by Northhampshire and to the west by Buckinghampshire.

The name Odell comes from the old English words “wad” or “woad” (a plant collected for

the blue dye produced by its leaves), and “hyll,” (hill). Julius Caesar reported that the Ancient

Britons stained themselves with woad. Woadhull, meaning the hill where woad grows, eventually

3

12 Families - An American Experience,

by William L. O’Dell;

The Odell Genealogy, odellclan.homestead.com/geneology.html/;

Family History, Swyrich Corporation, certificate #87862005198,

www.freecoatsofarms.com/house

offrames/;

Old

Families

of

Westchester,

freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/-vantasselfamilyhistoryhomepage;

geni.com/people/Walter-Flandrensis.

Page -5-

became Odell in the sixteenth century. The name has been spelled in many ways, including Odell,

O’Dell, Odle, Odehull, Wahul, Wodehull, Wahell, Wodhull, and others, over the centuries, as church

officials and scribes recorded names as they were told them, rather than following any spelling rules

or conventions.

4

The village of Odell is north of Bedford, in Bedsfordshire. It began as a farm before the

Roman conquest, although it was abandoned in the 4

th

century because of Viking raids. It was

unoccupied until the 6

th

or 7

th

century, and by the 11

th

century, there was a village there originally

known as Wadelle or Wadehelle, meaning “the hill where woad grows.” Before the Norman

Conquest, the land was owned by Levenot, a Thane of King Edward the Confessor. By 1575, the

village was referred to as Odell.

In 1066, William the Conqueror defeated the Anglo-Saxons in the Battle of Hastings and

took control of England. William granted to Walter Flandrensis, the Count of Flanders, who fought

alongside William at Hastings, “a great Barony” in Bucks, of which Wahull or Woodhull was the

chief county seat, as a reward for distinguished military services in the conquest of England. Walter

became the first Baron of Wahul/Woodhull or Odell. One account says that William was married

to Walter’s sister. Walter claimed that he could trace his family back to Priam, the King of Troy,

to about 1,200 B.C. After the Battle of Hastings, Walter built castles, roads, and walls for William.

Walter was first mentioned in 1068, and is often referred to as Walter de Wahul or Wodhull

(variants of Waldenhelle). This began a period of centuries where families bearing an Odell-type

name ruled over those lands.

4

One source claims that the Odell stock was originally Phoenician, and the women reported to the

tribe of Benjamin or Levi. This source says the family originated about 625 B.C., at what later was

called the city of Odellum, meaning a dell or small valley with a stream flowing through it.

Page -6-

Around 1068, Walter built a “motte and bailey” castle with a stone keep on the hill in Wahul,

with raised earthworks surrounded by a protective fence. Motte-and-bailey castles were introduced

by the Normans after the conquest, and around 1,000 were built in England. A motte is a mount,

generally artificial, topped with a wooden or stone structure known as a keep. A bailey is an

enclosed courtyard surrounded by a wooden fence or palisade, which was used as a living area for

servants of the castle and contained craftsmen shops. Some of these castles had drawbridges.

Walter’s castle became the seat of the Barons of Odell or Wahell, and his family lived there for 500

years. There are no remaining illustrations of Odell castle.

5

The Odells became a notable English family in Bedfordshire, seated as Lords of the manor

and estates in that shire as descendants of the Baron Walter of Wodhull. The family appeared in the

Domesday Book, a census compiled in 1086 A.D. by William, Duke of Normandy. The name also

appeared in the Ragman Rolls (1291 - 1296) collected by King Edward 1

st

, the Curia Regis Rolls,

the Pipe Rolls, the Heath Rolls, parish registers, baptismals, tax records and other documents. The

entire Odell family descended from Walter. Walter was related to at least four kings of England;

William the Conqueror, Alfred the Great, Edward the Second, and Henry VIII.

The Wodhull or Wahul family played a part in English history. Simon de Wahul was

described as an “invader” of Ramsay Abby, and he sided with Prince Henry in 1172, when the prince

rebelled against his father, King Henry IV. Simon’s son died on a crusade when he fell off a boat

at Acre. The family was part of the group of barons that required King John to sign the Magna

Carta at Runnymede in 1215, limiting the power of the king. The family was instrumental in making

the foundation for the Church of England and built many small chapels in England. There is a

5

en.wikepedia.org/wiki/OdellCastle.htm; en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motte-and-bailey.htm.

Page -7-

legend that the ghost of Sir Roland Alston still haunts the Odell castle. There is an Odell family

crest with a motto “Pro Patria Invictus,” meaning “For my Unconquered Country.”

Odell Village, Castle and All Saints Church

In 1633, the last Baron of Odell died without a male heir, and the castle and surrounding

property were sold to William Alston, a lawyer who was the Keeper of the Kings Bench, a post of

considerable importance. The title died out, and after 500 years, the village of Odell was no longer

ruled by a descendant of the family bearing the Odell name.

When Alston obtained the property, “[e]xcept for its earthworks, rising above the north ban

of the Ouse, their once impregnable castle had lapsed into strange ruins.” Alston built a Manor on

the castle site, incorporating the remains of the castle keep and oval moat held up by the retaining

wall. When William Alston died in 1638, the land passed to his brother Thomas, who became a

Page -8-

Baronet in 1642. His son inherited the land, but since he was born out of wedlock, he did not inherit

the title and it died out. The Manor was substantially altered and modernized in the 18

th

century by

Lady Wolstenholme. The interior of the Manor was redone, and the north-east and south-east fronts

of the house were rebuilt. Other alterations were done in 1864 - 65. Water for the Manor continued

to come from “King John’s Well” which was sunk to a great depth, over 60 feet to water level. An

extensive description of the remodeling work, and the Manor itself, was done under the Rating and

Valuation Act of 1925. The original Manor burned down in 1931, as described by the Bedfordshire

Times.

One of the most historic mansions of Bedfordshire, Odell Castle, was almost completely

destroyed on Tuesday. The Castle, which dates back several centuries, is situated in one of

the most delightful parts of the county, and stands on high ground overlooking the

picturesque River Ouse, from which a panoramic view of the surrounding countryside is

obtained. It has a wealth of historic associations, and in the reign of King John was used by

that monarch as a hunting box when the chase of wild deer took place in the extensive park.

The ruins of the Odell Manor and estate sold in 1934 to Lord Luke, and a new Manor house

was built in 1962, using stones from the old building. The site is still called Odell Castle.

6

Odell Manor built in 1633, picture by

Thomas Fisher from 1811

Odell Manor, 1863

6

www.bedfordshire.gov.uk/CommunityAndLiving/Archives/OdellCastle.

Page -9-

Odell Castle plan

Odell Manor, 1920

Odell Manor after 1931 fire

Page -10-

Odell Manor

Odell Manor built in 1962

Odell Manor and Church

Page -11-

Odell Estate from High Street

Odell Estate Building

Page -12-

Today Odell is a beautiful village of small houses built with locally quarried limestone,

several with traditional thatched roofs. Odell is “one of the most lovely villages in the wide and

winding Ouse Valley in this breezy rolling country of north Bedfordshire.” The Odell Great Wood

is nearby, “the noblest in the country.” The remains of Odell castle are there, along with a “striking”

15

th

century All Saints Church, probably the third church building to stand on the site, which

contains some ancient stained glass. The church,

an ancient, ivy-mantled structure, with a square towel containing a clock and five

bells...standing at a considerable elevation above the road, is a building of stone, in the

Perpendicular style, consisting of chancel, clerestoried nave, aisles, embattled south porch,

with groined roof, and a lofty western embattled tower with pinnacles and containing a clock

and 5 bells.

The western door of the church has indentations which according to local legend, are the Devil’s

fingerprints. The Devil wanted to get his hands on the wicked Sir Rowland Alston. When Alston

took sanctuary in the church, the Devil gripped the tower and shoot it in a blinding rage, leaving the

marks of his fingers behind.

7

There is a direct connection between Odell village and America. In 1635, the Reverend of

All Saints Church, Peter Baulkley, rebelled against the established church, and led his Puritan

congregation (including William Odell) to America where they founded the town of Concord, Mass.

7

Britainexpress.com/counties/bedfordshire/az/odell.htm; odellbeds.net/history.htm.

Page -13-

Odell Village and All Saints Church

All Saints Church, Odell

Inside of All Saints Church

Page -14-

Odell Village street scene

All Saints Church

Church and Odell Village

River Ouse from Odell Village

Page -15-

Odells Leave England

Religious and political upheaval in England in the 16

th

through 18

th

centuries led many

families to leave England, and Odells were early settlers in Ireland, Canada, the United States,

Australia and other British colonies.

Some Odells moved to Ireland as Protestant settlers and soldiers in Cromwell’s army during

the brutal reconquest of that country by forces of the English Parliament between 1649 - 1653. The

Irish Rebellion of 1641, freed most of Ireland from English rule. In 1649, the Irish signed an alliance

with the English Royalist party, which had been defeated in the English Civil War. Cromwell’s

campaign included many atrocities against the Irish, and estimates of the drop in the native

population range from 15 - 25% to half. Cromwell passed a series of Penal laws against the

Catholics and confiscated their land. Odells were granted lands that had been confiscated from the

native Catholic owners in Kilcleagh Park in Westmeath and Carriglea in Waterford, where the name

became spelled O’dell.

8

The first Odell or Odle in America was William (born in 1601), who came from the village

of Odell in Bedfordshire, England. According to one source, William was the younger son of an

English baronial family, who, along with his brother John, had to flee to America because he made

the mistake of siding with Lady Jane Grey against Mary, Queen of Scots. Another source says that

William and John were Puritans who immigrated to America in 1639, fleeing persecution from

religious intolerance. They were part of a wave of Puritan immigration between 1630 - 1640, due

to dissatisfaction with the Church of England. The Puritans wanted to establish their own church

and escape the harsh laws requiring them to be members of the Church of England. They were

8

en.wikipedia.rog/wiki/Cromwellian_conquest-of-Ireland.

Page -16-

called Puritans because they wanted to purify the services and teachings of the church. Many

belonged to well-to-do classes in England, and could set themselves up in the New World more

comfortably than the Pilgrims and early Virginians.

William Odell and his fellow settlers established the second permanent English colony on

Massachusetts Bay, Concord, which was the first settlement away from the coast. In 1644, 16

families from Concord moved to Connecticut, forming the village of Fairfield, including William

Odell (Odle). William died in Fairfield in 1676. The New England Historical and Genealogical

Register names William Odell as the founder of the Odell family in America. Some of William’s

sons stayed in Connecticut and founded the New England line of Odells. His oldest son, William

Odell, moved to New York and was one of 15 men who founded Rye, starting a New York line of

Odells. Issac Odell was listed as living in Westchester County, New York, in 1676.

Our Odell Line

The first Odell (or Odle) to whom we are related immigrated to this country around 1680,

according to the Odell family organization, was Austin Odell or Odle, who settled in Westerly,

Rhode Island. He was born in England around 1665. Records show that in the 1680s, Austin bought

30 acres of property in Westerly, R.I., a tiny settlement on the Pawcatuck River (the present

Connecticut border), 25 miles west of Newport. There is no record of his wife’s name, but it could

be Bradford.

Austin had at least one child, a son, Joseph Odell, born around 1690, in Westerly, RI. Joseph

married Elizabeth, whose maiden name also could be Bradford. They had at least four children: a)

Augustine or Austin Odell, born before 1711 in Westerly; b) Joseph Odell, born August 14, 1718

in Westerly; c) Levi Odell, born in R.I.; and d) Simeon Odell,(I) born in R.I., from whom our line

Page -17-

of Odells descended.

Simeon Odell married Mary Morey of Dover, R.I. They moved to north of New York City.

He died between 1810 and 1820, in Petersburgh, Rennselaer County, NY. Simeon appears in the

1810 census, but not the 1820 census. He also lived in Stephenson, which is now in Rennselaer

County, NY. Rennselaer County was created out of a part of Albany County in 1791. He also lived

in Stephentown, Albany County, NY. Again, that town is not now located in today's Albany

County. They also lived in Broadalbin, Montgomery County, NY. Simeon and Elizabeth had 12

children, including Simeon II (from whom we are descended), Mary, William, Lydia, Nathaniel,

James, Joseph, Betsy, Martha, Jonathan, Abigail, and Benjamin.

Simeon Odle or Odell (II) was born around 1757, and died circa 1820, in Greenwich Township,

now in Washington County, NY, a little northeast of Albany. This Simeon married a woman named

Elizabeth, who died in 1840, in Salmon, Hillsdale County, Michigan. They had eight children,

including Simeon (III), John Simeon, Nathaniel, Jonathan, Abigail, and Benjamin (from whom we

are descended). A family story was that the four sons weighed over 1,000 pounds.

Benjamin Odell (our grandfather’s grandfather) was born July 9, 1803, in Greenwich

Township, Washington County, NY. He died on Feb 9, 1890, in Van Buren Township, Onondaga

County, NY. Benjamin married Clarissa Knight, born Sept 18, 1806, in Onondaga County, NY, who

died Aug 7, 1859, Van Buren Township, Onondaga County, NY. They had five children, two who

died in infancy, and Harvey, Emeline, and Benjamin Bradford Odell Jr. (our grandfather’s father).

Benjamin Odell Sr. had a 180+ acre farm outside of Baldwinsville. He left 90 acres each to. Harvey

and Benjamin Bradford when he died..

Page -18-

Our grandfather’s father, Benjamin Bradford Odell, Jr., was born in Van Buren Township,

Onondaga County, NY on May 7, 1833. He died Feb 25, 1916, at the same location. Benjamin B.

Odell, Jr., married Mary Augusta Betts, a school teacher, who was born Jan 17, 1839, at Port

Gibson, Wayne County, NY, and died Jan 23, 1890, in Van Buren Township, Onondaga County NY.

They had four children: Ida, Clara, Mark (our grandfather), and Burr. They raised their children on

their farm outside of Baldwinsville, a village on the Seneca River and the 24

th

lock of the Erie Canal

near Lake Ontario.

9

Benjamin Odell, Sr., our grandfather’s

grandfather

9

Baldwinsville was settled in 1808 by Dr. Baldwin who build a dam across the Seneca River to

generate energy, and a private canal. It was incorporated in 1848. It was a local center for a

prosperous farming area with a grain mill located on an island in the center of town between the

Page -19-

Benjamin B. Odell, Jr.

Benjamin Bradford Odell, 1890s

Mary A. Odell

McHarrie Locks on the Erie Canal and the Seneca River. It was served by the Erie Lackawanna

R a i l r o a d

c o n n e c t i n g

t h e

v i l l a g e

t o

S y r a c u s e

a n d

O s w e g o .

En.wikepdia.org/wiki/Baldwinsville_New_York.

Page -20-

Mark and his brother Burr grew up together on the Odell farm. In a letter written to our

cousin Dick in 1962, Mark said that his sisters left Baldwinsville long before he did. His brother

Burr left New York after Mark did, lived in Florida, and had two sons. His sister Clara married

Gideon Simpkins and lived in Palmyra, Wayne County, NY. His sister Ida married Grant

Skellenger and also lived in Wayne County, but he died and she moved to Washington County and

married William Ham. Clara took a middle initial J., like Mark who took a middle initial M., and

Ida took a middle initial M. None of these initials were from the parents, but they added them later.

After high school, Mark graduated from the Baldwinsville Academy with a “classical

education,” studying Greek, Latin, Astronomy, etc. to become a school teacher. Mark received his

New York certification as a Third Grade Teacher on August 29, 1888. He taught at a local school,

eventually becoming its principal. Mark won a county essay contest and obtained a scholarship to

study at Cornell, which he attended from 1893 until his graduation in 1897. He rowed on its crew

of 1897, that won the national championship under its highly regarded coach Charles Courtney. He

attended Cornell law school starting in the Fall of 1897, but dropped out in March of 1898 to seek

his fortune in the gold fields of Yukon Territory, Canada.

Mark & Burr at farm

Page -21-

Odell farm house.

Odell farm house from back

Page -22-

Mark & Burr Odell

Burr Odell

Burr Odell

Mark Odell, 1890s

Page -23-

Burr’s wife Alice Stella Odell &

Elizabeth

Benjamin Bradford Odell & Elizabeth

Burr & his two children, Benjamin

Bradford Odell, Pennsylvania

Burr, Alice Stella, Benjamin Bradford

Odell, unknown man, and Burr’s

children, New York

Page -24-

CHAPTER TWO

ROWING AT CORNELL UNDER COACH COURTNEY

A. EARLY DAYS OF ROWING AT CORNELL

The early days of Cornell rowing are described in two books by C. P. V. Young,

The

Cornell Navy: 1871-1906,

published in 1907, and

Courtney and Cornell Rowing,

published in 1923.

The books are dedicated “To the ‘Old Man,” Charlie E. Courtney, whose coaching, and to the ‘Boys’

whose faithful training and earnest work, have combined to make Cornell pre-eminent in

Intercollegiate Rowing.”

The Rise of Cornell Rowing, 1871 - 1920,

by Eric R. Langstedt, published

in 2012, also describes the school’s rowing history. The school newspaper, the Cornell Daily Sun,

dating back to 1880, has been scanned and is available on line, and provides an insight into

occurrences on campus during those times.

10

Rowing at Cornell formally began in 1871, after a visit in the fall of 1870 by Thomas Hughes

of England, who created student enthusiasm to form a boat club. In the spring of 1871, two

competing boat clubs were formed which united under the name Cornell Navy. Cornell students

built a boathouse and acquired boats, including a six-oared barge (the Striped Pig), an eight-oared

barge (the Cornell), a four-oared outrigger (the Buffalo), and a six-oared outrigger (the Green Barge).

Cornell’s first regatta was in the spring of 1872, where the varsity and freshman crews beat

the visiting Navy crews. A Union Springs crew, in which well known local rowers Charles E.

Courtney and his brother rowed, won the race of the four-oared boats. That year, Cornell joined the

Rowing Association of American Colleges.

In 1873, Cornell received a new cedar shell from President White. Harry Coulter, the former

10

http://cdsun.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/newscornell?a=q&b=0

.

Page -25-

single scull champion of the United States and a professional rower, was hired as a trainer for

Cornell rowers. Coulter’s training schedules consisted of

long daily rows morning and afternoon, supplemented by an hour’s jaunt of walking and

running in the mid-day sun, dressed in thick flannel shirts and sweaters. Upon returning to

their quarters they were put into bed for half hour under several winter coverlets, preparatory

to a thorough rubbing down. The idea seems to have been to reduce every man in weight to

the last possible extremity. Even the drinking of water was forbidden, and we are told that

purgatatives were at times resorted to in order to bring about the desired results.

Indoor training consisted of work in the gymnasium on two rowing machines that had sliding or

greased seats, with a rope running through pulleys in the floor and the ceiling, and a weight in the

cellar.

11

Cornell’s hiring of Coulter upset the rowing community, because he had been a professional

athlete, resulting in an article about Cornell’s 1873 crew in a religious journal which put the issue

in moral terms: “[w]hen the pious lot was cast into the lap, the wicked crew [meaning Cornell] had

the worst position.” Later in 1873, the convention of the Rowing Association of Colleges decided

“not to allow in future the employment of professional trainers.”

12

In 1875, the local Union Springs crew which included the local rowing sensations, the

Courtney brothers, was invited to race against Cornell as a test of speed, with Cornell achieving “a

splendid victory.”

Cornell entered the big leagues when it rowed against Yale and Harvard in 1875 and 1876.

Cornell won both races, marking the school’s emergence into the rowing community and making

its oarsmen instant heros. The crews rowed in six-oared shells in 1875 and 1876. Cornell first

11

Young,

Cornell Navy,

pages 11

-

14

.

12

Miller,

Wild & Crazy Professionals;

Young,

Cornell Navy,

page 8

.

Page -26-

rowed in an eight-oared shell in 1878.

At the Saratoga Regatta in 1875, Cornell won the three mile race “with a final burst of

speed,” followed by Columbia, Harvard, Dartmouth, Wesleyan, Yale, Amherst, Brown, Williams,

Bowdoin, Hamilton, Union and Princeton. After the 1875 victory,

[e]nthusiastic Cornellians rushed into the water lifting the oarsmen from the boat, marched

them upon their shoulders up and down in front of the grandstand. Upon their return to

Saratoga the wildest demonstration ensued, and the Cornell oarsmen were the heroes of the

hour....A palace car was provided for the trip home, and the journey was a like a triumphal

procession. At Ithaca, a great arch had been erected on campus and the town turned out en

masse to join in the welcome.

The Cornell yell originated at the 1875 race. When the Cornell crew was leading the race, spectators

yelled “Cornell-ell-ell-ell, Cornell,” which was converted into “Cornell, I yell, yell, yell, Cornell.”

13

After the humiliation of losing to Cornell, Yale withdrew from the Rowing Association of

American Colleges in 1875, declaring that the natural advantages of Cornell were such that other

colleges could not hope to beat them. Harvard rowed against Cornell for one more year in the 1876

Regatta. In the 1876 Regatta at Saratoga, the finishing order was Cornell, Harvard, Columbia,

Union, Wesleyan, and Princeton. The winning Big Red rowers were welcomed in Ithaca with

“Cornell’s annual parade.” “Ithaca simply went wild upon their arrival, forming a procession a mile

long and assembling a crowd of several thousand persons in the park to hear speeches and join in

the celebration.”

Harvard withdrew from the Association in 1876, after its second consecutive loss to Cornell.

The

New York Times

chided them for taking this action:

It cannot be denied that the remarkable and altogether shameless conduct of Cornell in

making a clean sweep of everything in the [1876] Centennial Regatta is an excellent proof

13

Young,

Cornell Navy,

pages 17, 18.

Page -27-

of the sagacity of certain colleges in leaving the association and thus avoiding inevitable

defeat. New York is sorry that her colleges will row so famously that the New Englanders

have no other alternative to escape defeat than to flee from the encounter...We apologize to

the New Englanders for the intemperate conduct of young Cornell, that would not be

satisfied with anything short of all the flags, and commend them for their prudence in retiring

from a conflict in which apparently they consider they have no chance.

A writer at the time who was active in the rowing organization criticized the New England schools

for refusing to row against Cornell.

The humiliation of being beaten again and again by the young up start, Cornell, was agony

to the proud spirits of the New England colleges, who took the only means of escaping from

fresh indignity by withdrawing from the association.

Thereafter, for several decades, Harvard and Yale rowed only against each other in a self-declared

championship, refusing to allow others to join this exclusive club.

14

No varsity races took place in 1877 and 1878. Cornell lost both of its races in 1879, but beat

Pennsylvania and Columbia in 1880. In 1881, Cornell traveled to Europe to test its rower’s skills

there. The Big Red raced at the Henley Regatta in England, but lost all three contests in which they

entered. However, they were not allowed to race against other college teams, but had to race against

the best boat clubs in England. Cornell also lost a race on the Danube River in Vienna, Austria.

15

B. CHARLES COURTNEY BEGINS COACHING CORNELL CREWS IN 1883

Charles “Pop” Courtney was hired in 1883, to coach Cornell crews, and he led the school

to rowing success for nearly three decades.

Courtney, who was raised in Union Springs, N.Y. on the north end of Cayuga Lake, gained

14

Young,

Cornell Navy,

pages 19, 20; Cornell Sun, May 6, 1897.

15

Young,

Cornell Navy,

pages 21

-

25.

Page -28-

fame rowing near Cornell, and influenced Cornell rowing from its earliest days. In 1872, when the

school was only three years old, Cornell students talked about the “young countryman down the lake

who could row like the wind.”

Although successful, Courtney was a controversial figure because of patrician attitudes that

dominated sports in that era. Before coaching at Cornell, Courtney had been a successful amateur

rower, but turned professional to race Canadian champion Ned Hanlan in 1878. Courtney won all

86 of his amateur races. He only lost seven of 46 professional races in a time when oarsmen rowed

for “stakes” from regatta committees, and betting winnings. No one but Hanlan rivaled Courtney

as the greatest living oarsman of his day. Courtney won $450 on his first “amateur” race in 1873,

and there was a $10,000 stake in his 1877 race against Hanlan.

16

Charles E. Courtney as a professional

Charles Courtney & Ned Hanlin

16

Young,

Cornell Navy;

Miller,

Wild & Crazy Professionals.

Page -29-

Page -30-

Courtney, later known as the “Old Man” at Cornell, began assisting the Cornell Navy in

1883, by coaching part time, became its full time coach in 1889, and coached until his death in 1920.

He has been described as the “greatest training master of oarsmen in the world.” Courtney brought

with him the innovative “Courtney stroke” that influenced college rowing after 1897. In spite of

his success, Courtney was only hired year by year, at least initially, and all the funds to pay his salary

came from contributions made by supporters of rowing, and none came from the school. He was an

employed by the Athletic Association and had no official connection with the University. Other

colleges sought to hire Courtney away from Cornell by offering him larger salaries, so there was a

continual concern that he would leave the school. His loyalty to Cornell always prevailed.

Cornell’s hiring of Courtney drew significant criticism because he had been a professional

rower, even though Cornell had employed Harry Coulter, a professional rower, in 1873. The

New

York Times

editorialized:

If college boys cannot learn to row without association with persons like Courtney, perhaps

they would be quite as well off if they devoted a little more time to classics and mathematics

Charles Courtney in a single scull

Page -31-

and a little less to rowing.

17

This patrician attitude in sports was widespread in those times. Participation in the first

modern Olympics in Athens in 1896, was limited to gentlemen and the military; professionals and

the working class were excluded. Rowing first appeared in the Olympics in 1900, in Paris,

following this tradition.

18

Charles Courtney & 1883 Cornell crew

17

Courtney, Charles E., at HickokSports.com.

18

Crew: U.W.’s Most Successful, Stable Athletic Enterprise,

Seattle Post Intelligencer, 5/10/03.

Page -32-

In 1883, Courtney coached the Cornell crew for ten days, which “astonished the rowing

world” by beating Princeton and Pennsylvania by 32 seconds. The Cornell Sun of March 6, 1884,

reported that correspondence had been opened with Courtney “in order to make arrangements for

coaching.” Courtney coached the 1884 crew “for a period,” which he believed was faster than the

prior years crew, although Cornell lost two races to the University of Pennsylvania that year.

Courtney’s experience at Cornell during the 1886 season generated some conflict with the

school that was never fully explained. The Cornell Sun of February 15, 1887, said that “the crew

will undoubtedly have a professional coach in the spring and it won’t be the noted Mr. Courtney

either.” The Sun reported on March 3, 1887, that Cornell had hired “Teemer, the famous

professional oarsman” to coach the crew, who agreed to work for “a moderate consideration.”

Teemer would use the opportunity to train for double scull competitions. The article referred to the

coaching done the prior year.

We hope and believe that the navy’s sad experience with Mr. Courtney will not be repeated

with Mr. Teemer. The latter has a reputation for honesty and fair dealing that should inspire

confidence in him.

By 1888, whatever conflict there was between Courtney and Cornell was over and he again

coached its crew. Controversy continued, however. In September 1888, an article appeared in

Outdoor Magazine criticizing Courtney for conduct at one of that year’s races at Sunbury,

Pennsylvania in July.

The withdrawal of the Cornell four on the account of the alleged illness of one of the crew,

caused considerable comment. They won the Downing Cup at Philadelphia, July 4, and went

to Sudbury with the idea that they could repeat their Independence Day victory, but

withdrew, it is intimated by the advice of their trainer, Charles E. Courtney. It is unfortunate

that the Cornell crew should have the bad fortune to have this man as a trainer. His name

produces, whether justly or unjustly, an unpleasant feeling. He has scarcely ever been

engaged in a contest himself that had not ended more or less unsatisfactorily. This fact must

Page -33-

be well known to the oarsmen of Cornell, and if any amateur critices [sic] them for

withdrawing at the last moment, they must remember they are coached by a man who has

made an unenviable reputation in the annals of boat racing. The less amateur oarsmen have

to do with professionals the better. By the way, we thought there was an agreement arrived

at between college amateur some time ago discountenancing the employment of professional

coaches. How is this?

This letter was republished in the Cornell Sun of November 21, 1888, along with a defense of

Courtney. The article explained the illness of the rower that led to the crew’s withdrawal from the

race, arguing that Courtney had nothing to say about it.

The respect in which Cornell holds Courtney is well shown by the fact that he has been

engaged as coach and trainer for next year’s crew. Courtney’s reputation as an oarsman is

world renowned. He is a competent coach as was well shown by this year’s crew. His

magnificent offer to next year’s crew shows the interest which he takes in Cornell, and how

little personal interest entered into is work here.

The article ended by saying there was no agreement between Cornell and any other college not to

employ professional coaches, and professionals were employed at other prominent colleges.

Charles Courtney was hired as Cornell’s permanent residential coach in 1889, although the

school announced its decision to hire him before talking with Courtney. The Cornell Sun of March

1, 1889, reported that Courtney was

greatly surprised at the report that he was to coach this year’s crew, and said he had not been

spoken to, at all, in regard to the matter. He has had offers to coach other crews this season,

but has, as yet, accepted none of them. He would not attempt to underbid any other

candidate for position of trainer, but if he was wanted, he would endeavor to put a winning

crew on the water.

On March 8, 1889, the Sun announced that Courtney had been engaged to fill the position of

Cornell’s crew coach for another year. The Cornell Sun of January 7, 1890, announced that

Courtney was hired to coach for yet another year, even though he had received a more lucrative offer

to coach elsewhere.

Page -34-

The navy is fortunate in securing Courtney, under whose training a race has never been lost,

for he has received several big offers, one from the “Ariels,” of Baltimore, of $70 per week;

but although Courtney receives not half as much from Cornell, he comes here because he

likes “our boys” and because his reputation has been identified with “those fast crews from

Ithaca.”

Because of the success of Coach Courtney’s rowers, a new boathouse was built on Lake

Cayuga in 1890, to provide state of the art facilities for the crew. The class of 1890 donated $500

for the new boathouse, and the fund swelled from “generous friends of the University,” to build the

facility which would be “worthy of the champion college crews of America.” It was located on the

east shore of the inlet, within a few feet from the railroad, making it easy to load shells for

transportation to races elsewhere. The boat room was big enough to store a dozen eight-oared shells,

and opened onto a float for easy access the water.

19

In 1892, crew supporters provided Cornell’s coaches with a state of the art steam-launch for

their use. The Cornell Sun of November 15, 1892, reported that instead of constructing a steam

launch in Ithaca, a firm in New York had made “a splendid offer of a speedy launch.”

19

Young,

Cornell Navy,

page 32; Cornell Sun, October 21, 1890

.

Page -35-

Courtney became a famous and beloved figure at Cornell, coaching until 1916, and poems

were written in his honor.

In future when the windless lake is still,

and sounds of evening bells float from the hill,

when skimming shells in straining practice fly

up past the western shore, with coxswain’s cry,

and oarlock’s rhythmic throb and wash of oar,

‘The Old Man’ in his launch will come no more.

He dwelt among us without blame or fear,

and trained his oarsmen many a zealous year;

He taught them manhood also; how to meet

their fate, unspoiled by triumph or defeat.

‘Row hard! And may the best crew win,’ he said;

And victory hovered ever ’round his head.

Alas, the crews, the lake, the changing shore

shall see ‘The Old Man’ in his launch no more.

20

Charles E. “Pop” Courtney, Cornell’s famous rowing coach

20

Young,

The Cornell Navy: 1871-1906.

Page -36-

C. ODELL’S ROWING EXPERIENCES AT CORNELL: 1893 - 1898

Mark Odell began his studies at Cornell in the fall of 1892, graduated in June 1897, then

entered Cornell law school where he stayed until March 1898, when he and his best friend, Ellis

Aldrich, dropped out of law school and left for the Klondike Gold Rush.

While at Cornell, Odell rowed under coach Charles “Pop” Courtney, dividing his time

between academics and athletics. Odell was 6 feet tall and 184 pounds, which was big for his era,

and rowed five seat on the starboard side for the Big Red crew of 1897. Odell’s coach, Charles

Courtney, has been described as the “greatest training master of oarsmen in the world.” Between

1884 and 1895, because of Courtney’s coaching, Cornell’s varsity crew was undefeated, a series of

victories “perhaps without parallel in the history of college rowing.”

Odell’s 1897 crew established Cornell’s national rowing reputation after the school had been

overshadowed by Yale and Harvard for decades. The Big Red crew of 1897, won a three way

Regatta at Poughkeepsie, New York, racing Harvard and Yale for the first time in 20 years. To

everyone’s surprise, Cornell handily won and became “champions of America.”

New York Journal

,

June 25, 1897. Cornell beat heavily favored Yale and Harvard in this four mile race, establishing

the school as a rowing power, earning it new respect, and establishing the Courtney stroke as the best

and most efficient method of moving a boat. Cornell dominated college rowing for over a

decadethereafter under Courtney’s coaching.

The Cornell Sun of February 6, 1891, described Courtney’s philosophy and approach to

coaching that made his crews so successful, which were radically different from other coaches.

Instead of putting the men into rigorous training from the start and keeping them in it until

after the race, he adapts the exercise to the man. He trains a man according to his mental,

moral, and physical capability...”I would not have a man in training who had not good moral

Page -37-

habits: and those who drop behind in their University work - I drop.” He believes that the

mental make up of a man is just as important as his muscle. He can tell by a man’s speech

as much as by looking at him what he is worth in a crew.

The Cornell Sun of June 16, 1894, described other reasons for Courtney’s success.

His knowledge of the art of rowing, the skill shown by him in selecting “good timber” for

a crew, his cleverness in rigging a boat and seating each man, and his unselfish devotion to

the oarsmen placed under his care, win for him their respect and complete obedience to each

and every requirement...He is a strict disciplinarian, and has ever believed that conscientious

training is a great factor in the success of his “babies.”

Young gave his evaluation of Courtney’s success in his book,

The Cornell Navy: 1871-1906

.

This may be said to have been largely due to the excellent coaching of Charles E. Courtney.

Although his position as permanent coach did not begin until the year 1889, yet he assisted

in the training for five or six years previous to that time, and his advice had been a

determining factor. His methods, it need hardly be said, were those suggested by common-

sense. He was constantly learning, and this knowledge backed up by skill in building and

rigging boats, and splendid judgment in the selection of crews from the available candidates,

soon combined to establish at Cornell a system which will probably continue as long as

intercollegiate rowing exists.

21

Cornell Struggles to Keep Courtney as its Coach and Seeks to Race Yale & Harvard

During Mark Odell’s time at Cornell, the possibility of a race against their old foes, Yale and

Harvard, was a continuing issue, with those two institutions continuing to refuse to row against the

Big Red. Further, there was a constant struggle to keep Charles Courtney as Cornell’s rowing coach,

since he was hired on a year to year basis, and his salary and expenses were paid by student

donations, always an unreliable source.

In January 1893, there was discussion of an international rowing regatta to be held in

Chicago, where Oxford and Cambridge would row against America’s best crews. However, Yale

refused to participate.

21

Young,

Cornell Navy,

pages 26 - 28

.

Page -38-

The spirit displayed by Yale men in regard to the proposed international collegiate regatta

next summer is most peculiar...It would appear that the athletic men of that institution are

carrying the idea of exclusiveness too far, and will bring themselves into a bad light by their

attitude. Everybody is anxious to see the college crews of England and America but Yale

men announce that they desire to have the race confined to Harvard, Yale, Oxford and

Cambridge, and they especially mention Cornell as the college which they do not want to row

against...

It is a curious fact that it is only in aquatics that Yale fights shy of Cornell. In football or

baseball, in which Cornell acknowledges herself inferior, Yale has no objection to contesting

with the Ithaca boys: but when it comes to rowing, the wearers of blue decline to contest with

a crew which has not been beaten on the water for 10 years and which has a record fo 16

straight victories.

22

During the school year of 1892 - 1893, Odell’s first year at Cornell, there was continuing

concern that Coach Courtney would be lured away by some other school. The Cornell Sun of April

1893, reported a rumor that Courtney would accept a coaching position at Stanford University.

Courtney said he was planning a trip out west, and would “endeavor to be of some assistance to the

ambitious oarsmen of the West.” However, he said this would be just a vacation, and he “never had

the slightest idea of leaving the university most dear to him.” The Sun of April 25, 1893,

interviewed Courtney about his trip west. He said “if Leland Stanford Jr., University have a crew

he will go West to coach it and also the crew of the University of California later in the summer.”

The Sun hoped that Courtney would return to Cornell the following fall.

In 1893, Cornell’s experimented with rowing an aluminum eight-oared racing shell, designed

to carry an average weight of 175 pounds a man. The shell weighted 175 pounds, 25 to 50 pounds

lighter than conventional shells, and it was predicted to be “ten seconds faster than a paper shell.”

The experiment did not work - “the change did not commend itself as being advantageous.” That

year, Cornell beat Pennsylvania in a race held in Minneapolis, participating there despite being

22

Cornell Sun, January 5, 1893.

Page -39-

severely criticized for going to a local regatta “in the wild and wooly west.”

23

The Cornell Sun of October 6, 1893, described the yearly struggle to keep Coach Courtney

at the school, in an article called

Cornell Can Keep Courtney.

The Cornell Navy was in debt $1,400,

and had only raised $1,000 the prior year. Courtney was interviewed to learn under what conditions

he would remain coaching at Ithaca.

Much as Mr. Courtney loves Cornell, he very justly feels unable to remain here and coach

the crews unless his position is made secure. It is impossible for the navy to guarantee what

is required unless the students come forward and back it up with solid cash. The Athletic

Association has not the power to make this guarantee. Mr. Courtney agrees to remain at

Cornell for the year 1893-94 under the following condition, that his salary be $1200 to be

raised before October 11, on which date he must answer certain outside parties who desire

to employ him. He also agrees to remain at least four years after 1893-94 provided the

Athletic Association shall, by July 1894, be able to guarantee him $1500 a year. It is the

recommendation of the committee that every effort be made to raise $1200 in cash and $1400

in subscriptions before October 11.

The following plans for raising this sum is proposed by the navy and endorsed by the

committee: that a reliable person be stationed at the door of the Library to receive money and

subscriptions on and after Friday. And that the following committee have means for

collecting the business managers of the Era and the two college dailies, the presidents of the

three upper classes and the chairman pro tem of the freshman class.

On October 11, 1893, the Sun reported that $936 had been collected for the guarantee fund,

but $1,200 had to be raised before Courtney would agree to stay. However, the next day the Sun

reported that Coach Courtney would stay to coach, since over $1,200 had been contributed by

students, and other gifts from alumni and friends raised the total to $1,500. Courtney was pleased,

but had not waited for the funds to be raised and had declined the offers to go elsewhere. Courtney

also discussed the prospects of the Cornell football team, which he was helping to train.

The Cornell Sun of November 29, 1893, reported rumors that Courtney would coach

23

Cornell Sun, April 19, 1893; Young,

Cornell Navy,

page 33.

Page -40-

Harvard crews that year, saying he regarded the material at Harvard to be vastly superior to that at

Cornell. However, when interviewed, Coach Courtney denied making any arrangements with

Harvard, and said he would stay at Cornell until after the races next spring. “Cornell had the first

claim on me and here I would remain.”

The Cornell Sun of October 23, 1894, discussed the ongoing struggle to raise money for

Coach Courtney’s salary.

A dollar invested in Courtney’s salary will advertise the University more that a dollar

invested in any other way. Note it down as a nine o’clock for Wednesday - “Put my money

for Courtney’s salary in the contribution box.”...Do you know that Courtney don’t receive

any salary but what the Navy pays him; that his work with the other athletic teams is not paid

for except as you pay his salary of $1200.

In the fall of 1894, there was a discussion of holding an international regatta in the United

States in which all of this country’s best crews would compete against crews from the English

schools. However, once again, Yale presented an obstacle. The Cornell Sun of November 1894,

talked about “the annual grist of rumor about a race with Yale.”

For years, Yale has persisted in ignoring the Ithaca University crews, and would probably

continue in the same vein were it not for an obstacle that has suddenly arisen, and has placed

Yale in an odd situation.

Yale continued to try and organize a regatta where its crew and that from Harvard would row against

Oxford and Cambridge. However, Oxford refused to row against any crew except the “best in

America.” Oxford said it would only row against the winner of races between Yale, Harvard,

Cornell and Pennsylvania, throwing a wrench into Yale’s plans. That year, Cornell beat Penn in a

four mile race in what was “considered [a] remarkably good time.”

Intercollegiate Rowing Association is Formed

& Tournaments Begin in 1895

In 1891, Cornell, Columbia and Pennsylvania had adopted a constitution for a new collegiate

Page -41-

rowing association that became known as the Intercollegiate Rowing Association (IRA). Harvard

and Yale had been focused on competition between each other for many years, so these three schools

decided to arrange their own rivalries in a similar way. However, it was not until spring of 1895, that

the schools organized the first annual intercollegiate championship regatta to take place on the

Hudson River at Poughkeepsie, New York.

24

Problems for Cornell’s crew program emerged in June of 1895, when a fire destroyed

Cornell’s new coaching launch which had cost the navy over $6,000 the previous year. “She was

the pride of Courtney, being the best and fastest coaching launch afloat.” Cornell Sun, June 19,

1895.

The first IRA Regatta in June of 1895, was held in rough water, and water filled all three

shells. The Pennsylvania boat swamped and dropped out of the race. The Cornell boat took “a great

deal of water” but continued to race. However, Columbia beat Cornell by sixth lengths with long

smooth strokes. The IRA Regattas were a four mile course until 1919, when the IRA race was

shortened to three miles.

25

In July 1895, the Cornell crew went to the Henley Regatta in England, to compete “with the

leading rowing colleges of Great Britain for the championship of the world.” $10,000 was

subscribed by Cornell boosters to pay for the trip. Ithaca sent the Cornell crew off to Henley with

a parade in which Odell participated. He is on the far right of the front row in the second picture.

24

Langstedt,

The Rise of Cornell Rowing,

pages 116, 117.

25

Langstedt,

The Rise of Cornell Rowing,

pages 121, 122; Young,

Courtney and Cornell

Rowing;

Page -42-

Parade for Cornell’s Henley crew, 1895

Parade for Cornell’s Henley crew, 1895

Page -43-

Although Cornell’s crew went to England believing they would “make a fine showing,” they

were beaten by crews from Trinity and Cambridge after a Cornell rower caught a crab, knocking the

oar out of his hand, “causing the crew to go to pieces,” losing the race in disgrace. This experience

was hard for Cornell to accept. The losses in 1895 at the IRA Regatta and at Henley, meant that

after ten years of winning, Cornell was at last was defeated in two races in a single year. The

almost unbelievable news was sent out and thousands of Cornell enthusiasts had the blues

for days after. It was so unexpected it did not seem that it could be true...It was always

believed that Cornell lost both her races in 1895 by a combination of unlucky circumstances

and there grew up a mighty resolve that the defeat should not be repeated.

26

In the winter of 1896, Cornell women, inspired by the success of the men’s crew, sought to

have a women’s rowing program started. The Cornell Sun of January 22, 1896, reported that a

lengthy petition was submitted by the women of Cornell to the Athletic Council asking that Coach

Courtney be permitted to instruct them in rowing. The plan was to secure a safe boat, erect a boat

house, and “foster rowing interests among the women.” Courtney was willing to instruct them as

long as it did not interfere with his regular crew work. This was the result of a two year effort that

had the support of President Shurman and other faculty. “The Wellesley crew will be taken as a

pattern since rowing at that institution is a decided success.” The Athletic Council was to consider

the petition.

27

26

Young,

The Cornell Navy,

pages 35 - 38.

27

A follow up article appeared in the Cornell Sun of April 23, 1898. Since 1896, the Sage

College Rowing Club had been started, and was seeking funds to build a boat house. Miss Hill, the

physical director at Wellesley College took an interest in the boating club and “tried to enthuse the

women.” The club began in January 1897, and was admitted to the Sports and Pastimes Association.

The club began with 15 members, with women who did know how to swim taking lessons. The

women took machine practice at Mr. Courtney’s house until weather permitted them to go out on

the inlet. “Mr. Courtney’s directions and generous interest have been the greatest source of

encouragement the club has found in its up hill work, and his services cannot be too highly

appreciated.” A barge was built for the women, paid for by subscriptions. Three to four workouts

Page -44-

Anti Times Star, May 14, 1897

The issue of whom Cornell would race was a continuing debate. In 1896, a disagreement

between Yale and Harvard led to an agreement being signed between Cornell and Harvard to race

against each other for two years. Columbia and Pennsylvania consented to having Harvard invited

to participate in the IRA Regatta of 1896, making it a four way race. On January 16, 1896, the

a week were held at six thirty in the morning. Before the end of the year, they rowed fairly well. In

the fall of 1898, there were enough of the old club to continue practices. Courtney strongly

supported women’s rowing. “His directions and generous interest continued to be the greatest source

of interest throughout all the years which followed.” Courtney’s interest in women’s rowing is not

surprising, since his first job as a trainer in 1875 was “with a class of young ladies from the Seminary

at Union Springs.” Coach Courtney also strongly encouraged intramural rowing, believing that

coaches should not just focus only on varsity training, but should encourage fitness generally and

supervise all students who choose to row. He did this in spite of the fact he was always employed

by the Athletic Association and had no official connection with the University. “Mr. Courtney has

always regarded himself as a teacher of rowing and promoter of physical health, as well as a trainer

of crews.” Young,

Courtney and Cornell Rowing ,

pages 27, 63, 64.

Page -45-

Cornell Sun reported that Cornell had an agreement to row a four-sided race at Poughkeepsie against

Harvard, Columbia and Pennsylvania. The race would be four miles.

During January and February of 1896, the Cornell Sun regularly reported on the school’s

crew, and listed the candidates who were turning out for crew, naming Odell (who weighed 156

pounds) as a former crewman who had trained before, having rowed freshman crew. Courtney

wanted “more heavy men” for the crew. Throughout the year, Odell ended up rowing five seat on

Coach Courtney’s second varsity boat.

28

Cornell once again was concerned about Coach Courtney leaving the school. The Ithaca

Journal of February 7, 1896, reported on the possibility that Courtney would coach at the University

Cornell crew of 1896. Odell is in the middle row on the right. Coach

Courtney is the man in the circle in the upper left.

28

Cornell Sun, January 10, 25, & February 16, 1896.

Page -46-

of Pennsylvania. However, the Cornell Sun of February 8, 1896, confirmed that the rumor was not

true since Penn announced the re-hiring of Ellis Ward as its rowing coach.

The Cornell Sun of April 8, 1896, reported that a new shell made by Rough, the English shell

maker, had arrived. It was made of cedar with silk decks, and weighted 10 to 15 pounds more than

a “paper shell.” The paper said on May 8, “the side arrangements of seats give it a very odd

appearance to the rowers. It will not in all probability be used in the coming season.”

Cornell was the local favorite at the 1896 IRA Regatta at Poughkeepsie. The Cornell Sun

of June 18, 1896, reported that the

people came out of their houses and cheered. Boys had brought fire crackers for the occasion

and as the crew came in sight the cracking began. Flags with the Cornell colors were seen

in many windows and from several flagpoles. The conduct of the crew last year must have

been the best to produce such a general good feeling from the town people.

Before the IRA race of 1896, Harvard was picked as the winner by Casper Whitney, the noted

sports correspondent for Harper’s Magazine, who called it “the fastest and smoothest crew on the

river.” However, Cornell won the race to redeem the school’s honor, by five lengths over Harvard,

with Pennsylvania coming in third and Columbia fourth by 20 lengths.

Every man who was able went to Poughkeepsie to see those two races of 1896, and the

students who could not go were parts of the great throngs that crowded every telegraph

office in the land, waiting for the bulletins which came in at intervals of a few seconds.

When the news flashes over the wires that Cornell had won and had in addition broken

Yale’s American record, a mighty shout went up in every city in the country.

29

D.

CORNELL FINALLY MANAGES TO ROW AGAINST YALE & HARVARD

IN 1897

Background of Cornell, Yale, Harvard Regatta of 1897

Cornell had last rowed against Yale and Harvard in 1875 and 1876. Even though Cornell’s

29

Langstedt,

The Rise of Cornell Rowing,

pages 127 - 130.

Page -47-

rowing program had only begun in 1870, it won both races marking the school’s emergence into the

rowing community, and making its oarsmen instant heros. After this humiliation, Yale and Harvard

withdrew from the Rowing Association of American Colleges, and only rowed against each other.

Thereafter, Harvard and Yale rowed only against each other in a self-declared championship race,

refusing to allow others to join this exclusive club, a self-righteous attitude criticized by the sporting

press and disliked by Cornell.

Cornell yearned to race against Yale and Harvard to show that it was in their league. The

Cornell Sun of January 19, 1888, discussed the state of collegiate rowing and the school’s objective

to obtain a race against its old foes.

The day of four-oared rowing is over. Perhaps all are not aware that the old intercollegiate

association is finally and permanently broken up. To the recent call for a convention, not a

single college responded. Cornell’s record in the association has been a brilliant one and she

comes out of it in possession of the cup. But however deserving we have been of praise,

however plucky and successful our crews have been, we have certainly not received just

recognition of it since the palmy days when Yale and Harvard withdrew from the association

with the excuse that “they had no show where Cornell rowed, and they would rather row by

themselves.” And they have been rowing by themselves, and the attention and interest of the

world has gone with them and remained centered upon them, for Cornell has had no rivals

worthy of her mettle. But things were allowed to take their course until now the desired end

has arrived of itself...[W]e have crossed the line with twelve crews astern, we have rowed

the greatest of crews, Oxford; we have filled our library so full of trophies that some have

to be rolled up and tucked away for very lack of room...

Now as to whom we shall row. It will probably be out of the question to get a race with Yale

or Harvard next summer. We must first show our quality with some crews that they feel they

can down, and if we beat them - and we must - then will Yale and Harvard be bound to

answer a challenge from us.

Cornell went on to gain a reputation as a rowing power racing against other colleges, in spite

of not being able to compete against Harvard and Yale. By 1895, it had been a decade since

Cornell’s crew had lost to any other college, and the “success of the Cornell crews during this time

Page -48-

created an enthusiastic alumni community.”

Before the racing season of 1897, the Cornell Sun printed an article called

History of Cornell

Aquatics

, which summarized the success of the Cornell Navy over the years.

In the twenty-six years of the life of Cornell boating, there have been twenty-six Varsity

races, of which Cornell has won eighteen. But the most incredible list of all was the stretch

from 1885 to 1895 when Cornell scored twenty successive victories on the water. Her

freshman crews have never suffered defeat...Her victories were numerous, and, in the face

of the charge that she was not pushed, records were broken by Cornell with a frequency

which was appalling to her opponents.

The Cornell Navy held two world’s records: one for one mile and a half, with a time of, 6 minutes

40 seconds; and one for three miles, with a time of 14 minute 27 seconds. It also held one American

record for four miles, with a time of 19 minutes 29 seconds, several course records, and also records

for freshmen races. The races from 1885 to 1895, were typically against Pennsylvania, and

Columbia, although Brown and Bowdoin competed in a few races.

1896 - 1897 - Cornell Finally Arranges a Race Against Yale & Harvard

Odell’s senior year extended from fall of 1896 to spring of 1897, and he rowed in the varsity

boat in its five seat. Most of the oarsmen in the varsity boat rowed in the 1896 IRA Regatta. The

year was again filled with the dream of rowing against Yale and Harvard, and events at those schools

were followed carefully.

The Cornell Sun of October 14, 1896, reported that Harvard was negotiating with “the

famous English coach” R. C. Lehman, since their prior coach was no longer acceptable to the

program, and “ the time has come for a complete change in coaching methods.” Lehman would

teach the “English stroke” which had made his Oxford and Leander crews “all but invincible on

English waters.” He would not come as a paid coach, but as “an amateur anxious to advance the

Page -49-

interests of his favorite sport.” The Cornell Sun of November 16, 1896, reported that Lehman

arrived at Harvard to begin his coaching, and that the famous Bob Cook would remain at Yale.

“With Courtney, Lehmann, Cook and Peet as coaches at Poughkeepsie next year, there would be a

boat race which would eclipse in interest any previous event of the kind in America.”

The Cornell Sun reported on the first ever class regatta ever held at Cornell on November 11,

1896, which “was as exciting an event of the kind as has occurred on the lake in some time.” The

‘97 boat (in which Odell rowed) and the ‘99 boat finished in a tie, cheered on by the large crowd of

rooters.

The Cornell Sun of January 19, 1897, said a “jollification” was held on January 25, 1897,

to celebrate the signing of a contract with Coach Courtney for a three year period. Two hundred

attended, and Mark Odell gave one of the speeches commemorating the event. “The meeting closed

with a rousing cheer for Courtney and the Cornell crew.” This was the first time that Courtney