When David Lloyd George was appointed Prime Minister of Great Britain in the winter of 1916 he inherited a nation beleaguered and disillusioned by war. The Battle of the Somme cost the British Army two men for every centimeter of ground gained and the public was inundated with reports of massive casualties and little success. A wave of pessimism washed over the Entente as the British were running short of allies. Russia was collapsing and the Italians required French and British assistance to defend their territory. American forces were not expected to provide any significant aid in the near future, and the French themselves witnessed a mutiny that affected almost half of the divisions in the French Army. After the disastrous Nivelle offensive in the spring of 1917 the British Army provided most of the weight on the Western Front as the French Army no longer remained an effective offensive force.

With the ascendancy of Lloyd George came a change in Britain's overall war strategy. Believing any offensive in the Western Front to be futile, the new Prime Minister focused on the preservation of the British Empire. No longer was the complete defeat of Germany necessary for peace as a negotiated settlement was expected. Britain's war goals then focused on the continuance of its naval superiority, the preservation of the balance of power on the continent, and protected access to its empire. While the former goals would outlast a settlement, Britain was weary of Germany's links to the Ottoman Empire and the threat it posed to the Suez Canal and oil resources in the Persian Gulf. The idea was to hold fast in Europe and wait for a decisive moment while reinforcing the security of Britain's empire and garnering chips for negotiation. This strategy was vigorously opposed by the commander of the British Army, General William Robertson who held that the war would be won or lost on the Western Front. Robertson challenged that Lloyd George was sacrificing effective military strategy for the sake of insignificant victories to boost morale and the dispute between the two split the British High Command.

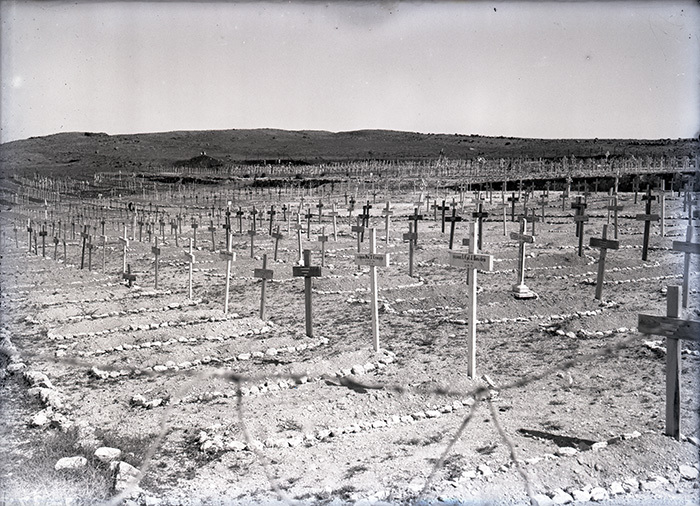

Nonetheless, General Edmund Allenby was sent to relieve General Archibald Murray as the commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in June of 1917 and was told to take Jerusalem by Christmas. He took over Murray's stalled offensive at Gaza, flanked the Turkish line at Beersheba and took southern Palestine by the end of the year, entering Jerusalem on December 11th. During the next year Allenby's force continually routed often smaller Turkish forces on their way to capture Damascus and Aleppo. The Palestine offensive was the last traditional cavalry campaign in modern warfare and one of the few overwhelming military successes of the First World War.

To the southeast, the 1916 revolt of Sherif Hussein, Emir of Mecca, offered the Allies another outlet to assault the Turks. Hussein's forces eventually removed the Turkish garrison from the Hejaz and dreamed of uniting all Arabs under their banner. The British and French generously funded the Arab nationalists and Hussein was able to gather an irregular army under the command of his son, Emir Faisal who was joined by a number British and French officers including Captain T. E. Lawrence. Lawrence was likely selected because his previous archaeological expeditions left him with a passable grasp of Arabic and the revolt often hinged upon which side was able to bribe the remote Arab tribesmen of a given region. Lawrence became a key advisor to Faisal and stressed the use of guerilla-style warfare against targets such as the Hejaz Railway. He and Auda ibu Tayi led the attack against an extremely light garrison at Aqaba with the support of the British fleet in July of 1917. It was during this assault that Lawrence accidently killed the camel he was riding by shooting it in the back of its head. Nonetheless, the capture of Aqaba allowed Faisal's forces to support Allenby's advance north into modern Jordan and Syria. Lowell Thomas arrived in the Middle East at the very end of 1917. He met Lawrence in Jerusalem in early 1918 and spent about two weeks on campaign with the young officer during the support of Allenby's march toward Damascus and Aleppo. His resulting travelogues became the primary way the campaign was perceived by the postwar world.

Marist University | Marist Archives & Special Collections | Contact Us